The Relational Poverty Network is a USA-based but internationally driven ensemble, which convenes a community of scholars to develop conceptual frameworks, research methodologies, and pedagogies for the study of relational poverty. It is a project inspired and managed by Vicky Lawson and Sarah Elwood, two scholars who have done much to help us rethinking poverty and care.

I’ve joined the RPN a few years back and they always have been incredibly generous to me, firstly promoting my documentary film and now inviting me to their fantastic series of podcast on ‘New Poverty Politics‘. The series includes some of the most exciting researchers, activists and practitioners working around poverty politics in the USA and beyond.

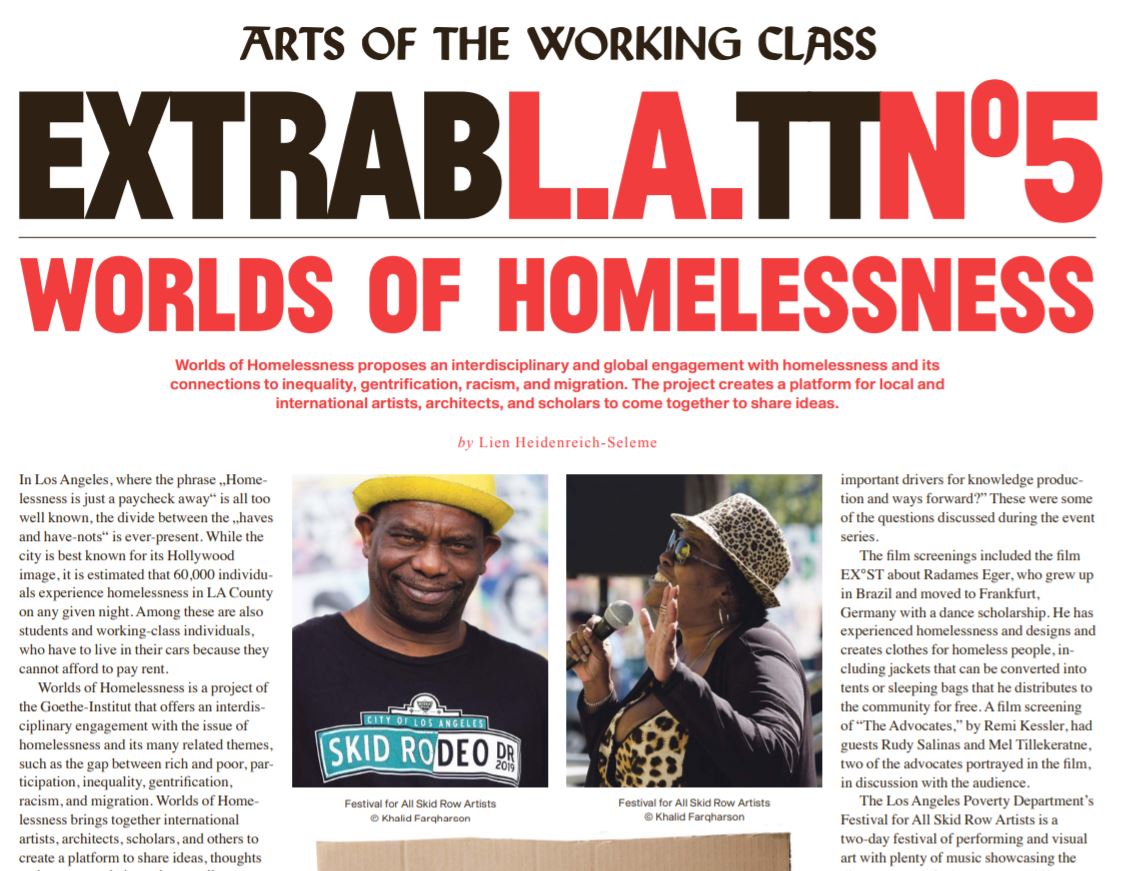

In ‘On Collaborative Art Praxis to Challenge Homelessness‘, Rhoda Rosen (School of the Art Institute in Chicago), Billy McGuinness (Museum of Contemporary Art Chicago) and myself have a conversation on challenging communities to engage homelessness through collaborative art praxis. You can read the transcript below and access the podcast here.

“New Poverty Politics for Changing Times:

What Emerging Nationalist Populisms Mean for Poverty and Inequality”

A project of the Relational Poverty Network

A conversation between Michele Lancione (University of Sheffield), Rhoda Rosen (School of the Art Institute in Chicago) and Billy McGuinness (Museum of Contemporary Art Chicago)

Rhoda Rosen: Hi, I’m Rhoda Rosen.

Billy McGuinness: And I’m Billy McGuinness.

Rhoda: And together we’re co-founders and co-directors of an organization, or we should say an artist collaborative, called Red Line Service. Red Line Service is the name of a train line in Chicago where many people find themselves sleeping overnight in this provisional space for want of appropriate, affordable housing in the City. On one hand, we chose the name because our first artistic interventions as an artist/curator team were with people with a lived experience of homelessness on the train platforms of this train line. But, we also wanted to complicate the term “service”, which implies a yucky hierarchical relationship of people with means and people “in-need” rather than a mutual recognition of humanity, which is what our art project aims to create and model. [as well as an artist collaborative???….]

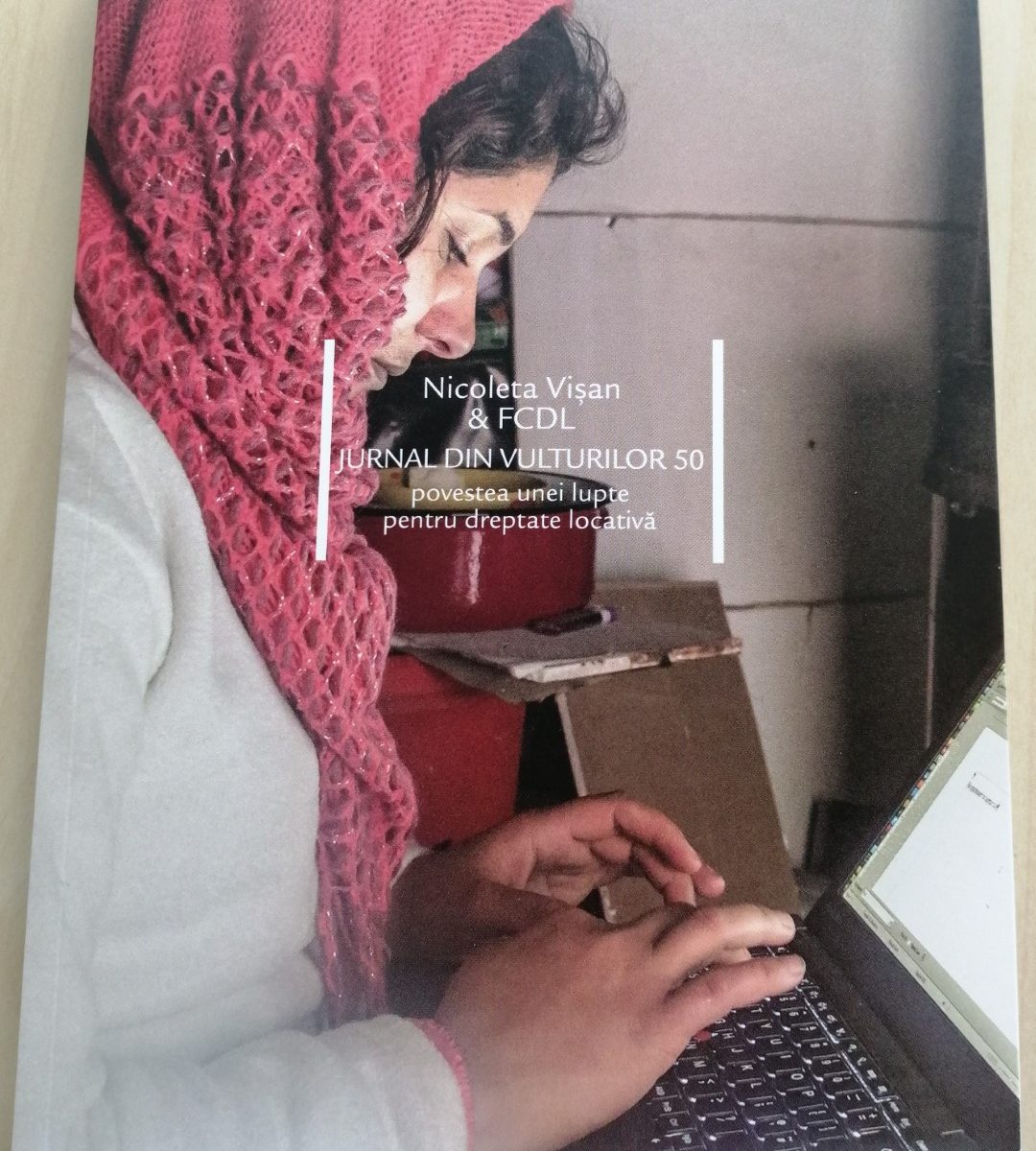

Michele: So my name is Michele Lancione. I am essentially an urban ethnographer. I do most of my research in relation to homelessness and in relation also to evictions. Recently I have been working around evictions affecting Roma people in Bucharest, Romania.

So probably we can start with the first question and I can ask you, Rhoda and Billy, to tell me something about: what are priority research topics on impoverishment in this moment, accordingly to you and your experience?

Billy: Well it’s a conversation we’ve been having over several years, I think. While Rhoda and I might each describe it differently, for us, we understand research to be a mode of action in the world: a way of relating to people, a way of working with people. And we also understand the work that we do to be a research practice, first and foremost. But it’s a research that is founded on direct interaction with the situation that we’re trying to learn something about, as opposed to pure observation.

Rhoda: Or as opposed to coming in with knowledge, we really see ourselves as in an unfinished, incomplete, and ongoing process of learning. And that for us is really important because every event or interaction we have, or community we engage with and build, and participate in co-building, we learn more and more. So our research is really active and always in process. And for us that’s how art is. So it’s something we can bring because we’re navigating through spaces all the time; we feel that the not-for-profit spaces, or pure academic spaces, can’t really bring that piece to the table.

Michele: This is very beautiful what you are saying. It’s actually – although I’m not an artist, I wouldn’t describe myself as such – it’s actually very close to the kind of understanding that I have of academic research and engagement. And I would say, at large, it’s my definition of being an intellectual. So you do things because you are part of those things and you change in the process of doing them. And in the process of doing research with vulnerable communities, in a sense, you are not trying to – or at least I’m not trying to describe them or to rise above them, but also always trying to do something that is empowering for both. So I think it’s very close to what you are saying. And I do agree that academic spaces, conventional academic spaces, are not ready, are not perfect; and they don’t really allow for that kind of encounter. So I think that creative methodologies and community-based activities are better in that regard. They allow for a better encounter to take place with people. Yeah.

Billy: Well it’s really refreshing that you understand us as well as you do, and that you share some of our values and approaches. Because, while I think there are people who are sympathetic and supportive of our way of working, and the people that know our project well are very enthusiastic, sometimes we feel like we’re all alone in this thing [laughs]. In prioritizing direct interaction with other human beings, sometimes people look askance at us and our approaches as being somewhat unconventional!

Rhoda: Mhm. And, you know, when you’re doing it as an art project, the frame is around something that’s happening in real life, right? The frame is really around an experience and that has been a challenge to communicate to, particularly, not-for-profit direct service organizations who are at the coalface, right? They are right there giving the person the shelter when they need it, or giving them the meal when they need it. But, they almost entrench a power hierarchy, rather than coming to the person on the level of equality and the desire to be open and to change yourself, as you said, which is critical to us. And, also they come, I think, with this understanding that the thing they are helping, homelessness, is more of a trait than an experience – a momentary, current experience. And so we really try to break open everyone’s possibilities – ours and the people experiencing homelessness. We try to help ourselves and others to reimagine our personal possibilities. And so, in that sense, it’s really a kind of re-centering of the voices of poverty

Michele: Well I think I’m going to quote what you just said. Yeah, “re-centering the voices of poverty,” it’s a beautiful way of putting it. And actually, what you said, both of you, it reminds me of the parallels that there are between, let’s take your example, not-for-profit organizations and their way of dealing with homeless people, or other vulnerable communities, and what the university does to us. Because, in a sense, these are both institutions. So they have, you know, clear mandates and, as you said, they are hierarchical. And they don’t allow, you know, for a true encounter with their constituencies, somehow. And I think that, yes, experimentation with creative writing or filmmaking can allow to disrupt some of these spaces and can allow to create new spaces in the in-between, no?

And this is what I tried to do. And I sense that it’s the same thing that you try to do. And it’s always a challenge, as you said. Because when you have your colleagues, your academic colleagues or maybe also within the artist community, looking at you as a foreigner, no? As a foreign element within their space. So there is a double challenge: there is the challenge of having to deal with an institution that is not designed to give you that space, and then also to deal with colleagues that do not recognize that what you are trying to do is still part of the intellectual labor that we are supposed to do as artists, intellectuals, and academics.

Billy: Yeah I love what you said and I think that the flipside of that liability, the liability of being a part of the system which we’re trying to change, is that when we do go into a community, or have an interaction with a population of people, our approach is so different than the institutions they’ve been working with. Precisely because we are a foreign agent in this otherwise understood order of things. We come along and we try to remove hierarchy as a first step before we’ve even walked into the room. And so, you know, I’m fresh from a conversation with a friend of ours that we’ve met through this work from a few weeks ago, who said, “when I met you and Rhoda, it was the first time since I became homeless that anyone didn’t treat me like a second class citizen. I walked in and I felt like an equal, and right away I said, ‘oh well this is different. These people are different.’ And that was what kept me coming back and wanting to have the experience with you.”

Rhoda: So I want to just say that I love what both of you are saying. And thank you so much, Michele, for bringing back the institution. I don’t disagree with the points you are making – you were speaking about it as an academic space not designed for experience. What I’ve also realized is that we have to bring our work to campus, because we also all teach, right? So we teach this kind of socially engaged art practice to students, and work with them on our projects, and with communities. And so we also have to remember that what’s happening in the outside world isn’t distinct from what’s happening on campus and to teach them engaged learning.

Additionally, we have sat in class and a student has said, “I was homeless for this many months or years or whatever.” And we’ve been to presentations in museums where a student came to us crying, saying, “thank you so much for speaking about this; my family” – in the suburbs, this was – “ we slept in the car for two years.” So remembering to know that our campuses are not ivory towers, there are people in the food pantries and in shelters who we deal with everyday on our campuses – and we have to make our classrooms also spaces where we can have those conversations .

And then, you know, to Billy’s point, I love that you brought that idea back too – that we are foreign agents within institutions: it’s not just a hierarchy that excludes a set of ideas. These experiences of poverty are within our campuses too. And when we forget that and assume a kind of privilege for all, that can be very difficult.

Billy: Yeah. I’m also just thinking of the experience, just going off of what Rhoda just said, you know, we had an event yesterday. One of the participants in our program is a PhD candidate who is getting his doctorate in Social Work, and he’s been participating in our program as a way to study and inform his research. And in yesterday’s event, he was just devastated at the end of it, in a good way. He was so moved; he was so challenged; he was so opened up by the experience – and you know he was really surprised by that, it really caught him off guard. And, of course, for us, it’s a bit like, “welcome to the party, man! We’ve been waiting for you to show up and realize what this work is actually about, and how deep it goes.” And the context of his revelation was a museum of African-American history in Chicago. And he’s African-American. And so we talked a little bit about how uncomfortable the space is, necessarily uncomfortable, when we’re having the most important conversations, the conversations that get at past trauma, whether that be on a personal level or a societal level or a global level – those things we’d rather not talk about. If we don’t create a safe space for that awkwardness, then we can’t look at those problems with any kind of honesty and we can’t effectively work to change the situation. And so for him to come, you know, at an advanced moment in his research, and just begin to learn.

Michele: This is, yeah, it’s very powerful. I think actually what we are saying, what you just said, Billy, it’s a possible answer to the second question that they posed us, which is: who should poverty researchers be collaborating with, and also how?

I mean essentially is very beautiful that we have this in common, although we we don’t know each other, is that to create the possibility of collaboration both the researcher and the community, or the people we are dealing with, needs to go outside of their comfort zones. So they really need to do what you just said, Billy, just like moving away from the comfort of what we know, and from the comfort of our established categories, and try to have a conversation from that discomfort. So, in a sense, the discomfort becomes the first step in order to be able to have the encounter that we were kind of evoking before. And I insist on this notion of the encounter, mostly because I am an ethnographer. And I think that before the “graphy” part of ethnography, which is the representation – and that representation can be done in academic form, but also in creative different ways, in artistic forms. Before that “graphy,” the “ethno” part is fundamental: which is exactly the encounter, the getting to know the other. And that encounter is possible only through that initial discomfort.

And also the discomfort, though, if you want, the conversation through Skype through different time zones, and so on and so forth. I don’t know you, I don’t know your faces, there is an initial discomfort. But still, it’s productive, it allows us to become closer. So I’m really enjoying this.

Billy: Yeah, that’s great. We feel the same way. I love that, yeah, the importance of the encounter -– and the crucial nature of the discomfort as a necessary first part of the process.

Rhoda: And maybe the end. I mean, I don’t know about the end point, but maybe the next step is, of course, the reciprocity. So when I think of old fashioned ethnography and what this person, this researcher, actually brought to us was “oh, I can’t participate, I’m here to observe.” But, in fact, that’s why it took him so long! Because as soon as he reached that discomfort and that openness, when he had the rug pulled out from under him, then the moment of an authentic relationship with people, with others – a reciprocal, rather than hierarchical, relationship with others was possible.

Michele: Yeah. I think that everything we are saying points to the next question that they are suggesting for us to tackle, which is: what are priority actions we should be taking to resist exclusionary trends? So we live in different contexts, and maybe you want to say something about a possible answer to this question in relation to your context? I mean the U.S., and Chicago, in particular?

Billy: It’s such a rich question. And of course I immediately think about – when I think about exclusionary trends, I think about equal and opposite trends moving in the other direction, right? And I’m answering really only for myself to say that I think insisting on – and I’ll use Rhoda’s language because I think she says this – “radical inclusivity” in our approach is a very direct and honest rebuttal of exclusionary trends that we’re seeing. To put inclusivity, a genuine inclusivity, at the front of the conversation. But I think to constantly challenge ourselves when we think we’re being inclusive to know that we’re not. To know that we can always open that door wider, expand that conversation further.

Michele: And for you, Rhoda, it’s the same, I guess? Or…?

Rhoda: Well, you know, Billy said that so beautifully and smoothly. It seems so simple to open a door, but it can be challenging! You know, we encounter a lot of mental illness on the streets. To back up to your point about Chicago: Chicago is a wealthy, yet bankrupt city sitting in the middle of a bankrupt state, not that this excuses closing mental institutions, rather than ending the corruption – but they have closed most of the state facilities and those people have been delivered to the streets. Our prison system, which Billy can speak more to, our Cook County Jail, is the largest mental health facility in the world.

Billy: And in fact, the three largest mental health facilities in the United States are all city jails: in New York, Los Angeles, and Chicago.

Rhoda: Right. And so we see the impact of those – of not just gentrification, not just the redlining that took place to ensure that Black families in the 60s and 70s wouldn’t be able to buy homes and keep them. The forced gentrification – as the city moves south and west into what were historically African-American areas, and watching people having to leave those. Automation, as well – you know, all of the contemporary things we see globally are being played out in a very heightened way in Chicago. And so, we plop down in the middle of that and say, “you know what? There are solutions, whether that’s housing first or paying people a living wage, and we’re just going to enact those as our art practice.” It’s that simple. And if two of us can do it, how much more if, as Billy likes to say, plumbers start caring or nurses start caring, or art historians start caring together, how might we enact real change.

Michele: Wow, this is very informative for me, that I don’t live in that context. There is one of the examples that you just made, Rhoda, which is housing first. I’ve been working a little bit on that in Italy, in ways. And there is one thing that has always struck me about housing first, is that: it doesn’t really require a huge economic investment. It doesn’t really require a huge managerial investment. What it really requires, the fundamental requirement – I don’t know if you agree with this – is a cultural change in the way you look at homelessness, no? So instead of looking at people from the point of view that they are not ready for it, you just look at them like, of course they are ready for it, no?

But this is such a big change. And I think that one of the ways – just to link my answer to the question – one of the ways to resist excusing these trends, from my point of view, from the work I do as an academic, is just to try to push these kind of radical agendas and policies in a very provocative way. I mean, in a sense, I tell my students, “just stop doing literature reviews.” I mean, of course, you need the literature review, but “start to think about what you are studying in a critical way, and also in a radical way.” And when I say “radical” I mean something that can be made active in the world, that is actually enabled by people in a sense.

So, in a sense, I mean a very stupid way of answering this question is that exclusionary trends, in a sense, can be resisted only by constructing non-exclusionary trends. And you construct non-exclusionary trends, as being an academic, just concerning yourself with constructing ways of making theory and policy radical: action enabled by people. You know, something that can be used by communities. Yeah, and everything you said, I mean, the scale is different, the context is different, the history is different – but many of the issues that both of you highlighted are very much present in the UK as well. And I think we can tackle them. We can try to find solutions to them only if we start to think critically at the jobs that we do; just don’t take things for granted. And as academics I think we have a big challenge, again, because the institutional tells you essentially, you know, to take things for granted – because you have to comply with the metrics, and you have to write papers, and be ranked. OK, now I’m just starting to, you know, babbling about everything, but yeah.

Billy: It’s very important what you’re saying! And I think that, you know, where you have those people who march in the street and yell about keeping out foreigners, you have the very easy target, right? OK, this is the opposition; these are the people whose minds we have to change. But, in fact, the grossness of their approach makes them easy to identify. The harder to identify exclusionary trend is the one that is unspoken and that lurks inside the most progressive institution, the most progressive work environment. You’ll find that little thread of, “yes, we’re lifting the masses but only to the bottoms of our feet and no further because we like our position here.” And so whether that’s the academy, or whether that’s, you know, a not-for-profit system that lives on charity from the for-profit system, or wherever you look, you can find that. Which is not to say people aren’t well intentioned. On the contrary, they’re incredibly well intentioned.

So the same admonition that you give your students about actionable approaches in the world that are radical in their actionability, that same shift in perspective that you’re working with your students to create in the context wherein you work, is applicable at a dinner table with your spouse and your extended family, is applicable in the classroom, on the street – everywhere we go. And it can be confrontational without being aggressive or assaultive. You can simply plant a new perspective in the conversation that requires a response. Even if it’s not a spoken response at that moment – something someone can take away and chew on for a while and say, “hmm, I’ve got something to think about.”

Michele: Absolutely.

Rhoda: Mhm. And I kind of just want to name ¬– I think I want to name the thing that we’re talking about when we say that we want to be inclusionary in a radical and authentic way. And I think it’s about this issue that you raised, Michele, about people assumed to be coming with deficits rather than coming with assets, right? And if you assume that people come with assets then, number one, they’re welcome. But what you’re really talking about is that you recognize – because I think that’s a really important word, to recognize – another’s dignity, that is inherent. And if we were to put our finger – and I’m speaking for you too, Billy – that if we were to put our finger on what we believe about every person who we encounter – it’s that we’re recognizing their dignity and we’re, in turn, recognizing our own dignity.

Billy: Yeah. I would take out the word “dignity” and replace it with the word “humanity.”

Rhoda: I like that. [all laugh]. I agree.

Bill: I think that’s the approach.

Rhoda: Right. Because dignity is filled with historical baggage, right?

Bill: Yeah, it’s got some baggage we don’t want to carry.

Rhoda: But it’s recognizing the humanity of a person, and in turn, our own humanity which is often lost when thinking about meeting people on equal footing.

Bill: Right.

Michele: Yeah. I agree with what you said, replacing with humanity. And I think, in the end it requires just training ourselves to it, in a sense, no? Because, I mean, what we’re talking about is also about empathy. To be humane with somebody else, I think, it means to understand where they come from. And that understanding requires an empathy that can be fostered, can be trained. So, in a sense, being attentive to what other people have to say and how they behave can be learned. It’s not something that we are born with necessarily. And I think it can be born, and to a certain extent it can be taught. So I don’t if you agree with this, but I think maybe one the priorities for critical poverty studies, just to connect to the last question, is probably: find a way to let people feel, more than understand, that empathy is necessary and it’s a prerequisite, probably, of action.

Billy: Well I love that you said that, “I don’t know if you agree with me.” I think that if I didn’t agree that empathy could be learned, it would be very hard to do this work [laughs]. Because I’m trying to learn it myself through this work. Yeah, that’s right, I believe we can learn it. Sorry, I got lost as you mentioned the last question – I had a response that was specific to that, but I guess I’m just really hung up on this idea that we have to be able to learn empathy. We have to be able to learn how to listen to one another, how to be with one another.

Michele: I’m curious to hear your response to the last question then, Billy.

Rhoda: Can you repeat the words.

Billy: Yeah, what was it?

Michele: I said I’m just curious to hear the response that you had for the last question, Billy.

Bill: Can you say that last question again? I don’t have it in front of me.

Michele: Oh sorry, sorry. It’s what are priority keywords for critical poverty studies in this moment?

Bill: I think “shared humanity” might be a good place to start as a keyword, sort of recognizing and participating in shared humanity.

Michele: And for you, Rhoda, it’s the same?

Rhoda: Mhm, mhm.

Michele: Yeah, it’s a difficult question. I find myself a bit lost when it comes to keywords. I kind of don’t know how to deal with them. So probably I would say something that was said before, like “empathy”, “radical action.” And maybe I would add to this becoming a little bit slower. Like “to be slow.” It’s another thing that I throw into the pot, because I am trying to learn that. To just try to slow down, and in a sense, by slowing down, allowing for that empathy to emerge. And maybe for reasons, nowadays, for me to enter into that discomfort, the discomfort zone we were talking about in the beginning, to enter into that zone I need to slow down. Because I am going so fast and doing so many things, like you, I guess. So, in a sense, slowing down may be another keyword – just trying to take time to listen.

Billy: Yeah. That’s right on. And something that I guess that occurred to me earlier, when I read through the questions, was something that we picked up from one of our friends in one of our programs. He said he didn’t like to think of himself as homeless; he preferred to use the term “in transition.” And that really struck a chord with us. And we started using it as the preferred term for anyone experiencing homelessness. And people in our circle caught on and started using that term; they referred to people in housing transition, people in transition. And maybe a year later I was with this man again and I said: “by the way, that word that you use, “in transition,” is that common among people who are experiencing homelessness, or is that just your word?” And he said, “oh that’s just my word; that’s just the word that I like.” I said, “well we’ve been spreading it around” [laughs]. But I love that word to be something that we recognize going into any situation – that it is a situation in transition, whether that’s a personal situation or a societal one; it’s always in transition.

And so we approach, as you say, slowly, deliberately, with our eyes wide open, with our ears open, hopefully – with the understanding that what we’re looking at is changing right before our very eyes through contact with us and countless other factors.

Rhoda: I like this. We’ve got: slow pace, shared humanity, empathy, assets rather than deficits. I love the active research.

Billy: And flux, a sense of flux.

Rhoda: A sense of flux. Authentic encounters, authentic relationships, maybe. We also talk about sometimes, in fact we’ve named a program something around, “disrupting the narrative.” It’s another way of saying that we’re determined to break what people think of as poverty. And, yeah, the expertise – maybe another thing is “changing the expertise.” People come with so much of that that we can’t hear if we lead with our assumptions.

Michele: Absolutely, I couldn’t agree more with the changing the expertise – starting with the academic expertise, and then of course going into the practicioning world. Yeah, changing the expertise, it’s fundamental. It’s actually, again, related to homelessness; it’s the key to change the way in which practitioners, or the media, day to day man on the street deals with homelessness.

Yeah I really enjoyed having this conversation. I just hope that sooner or later we will meet. When I come next to the US I will let you know, and I hope that you’ll do the same if you happen to come to the UK.

Rhoda: Great, yeah.

Billy: We will certainly be in touch about that. It would be wonderful to meet you into a person.

Michele: Yeah, the same. OK so we did it, apparently!

Bill: Wonderful! And it’s just 40 minutes since we started the call. [all laugh]

Michele: Exactly. So it means that we really liked it.

Rhoda: Right! Thank you so much, Michele.

Michele: No, thank you both, really. Thank you. Thank you very much. Have a nice day. Bye.

Rhoda and Billy: Bye.