In Italy, for migrants who do not request asylum, or for those to whom refugee status is denied, there are the Centri di Permanenza e Rimpatrio (CPR) (lit. Permanence and Repatriation Centres, once called Identification and Expulsion Centres). In these centres − which are essentially jails from which the asylum seeker cannot leave − individuals are restrained for a maximum of 18 months, without having committed any unlawful act, beyond not having the right document to be in the country. During this time, a judge needs to decide their fate. Either the asylum request, or any other favourable solution, is accepted, or the individuals are expelled from the country. Currently there are 9 CPR across Italy, with roughly 1,000 available places.

According to a study from a prominent Italian coalition in defence of civic rights, from June 2019 to May 2021, at least 6 individuals lost their lives while being detained in one of the ten CPRs across the peninsula. Thanks to the impressive investigative work of the Association for Juridical Studies on Immigration (ASGI), we know that the conditions of life in the CPR of the city where I work, Turin, defy any imagination. In their recent report, ASGI tells stories of an man with broken legs to whom the police denies even a simple crutch, obliging him to lay down constantly; another who shows proof of a rare blood diseases when admitted to the centre, and will have to wait 49 days before receiving any medical care; or the case of a third young man, who self-declares as a minor (therefore someone who could not be detained in a CPR) but is not believed, and is kept in the centre for 95 days, without explanation before he eventually decides to cut himself on his right arm.

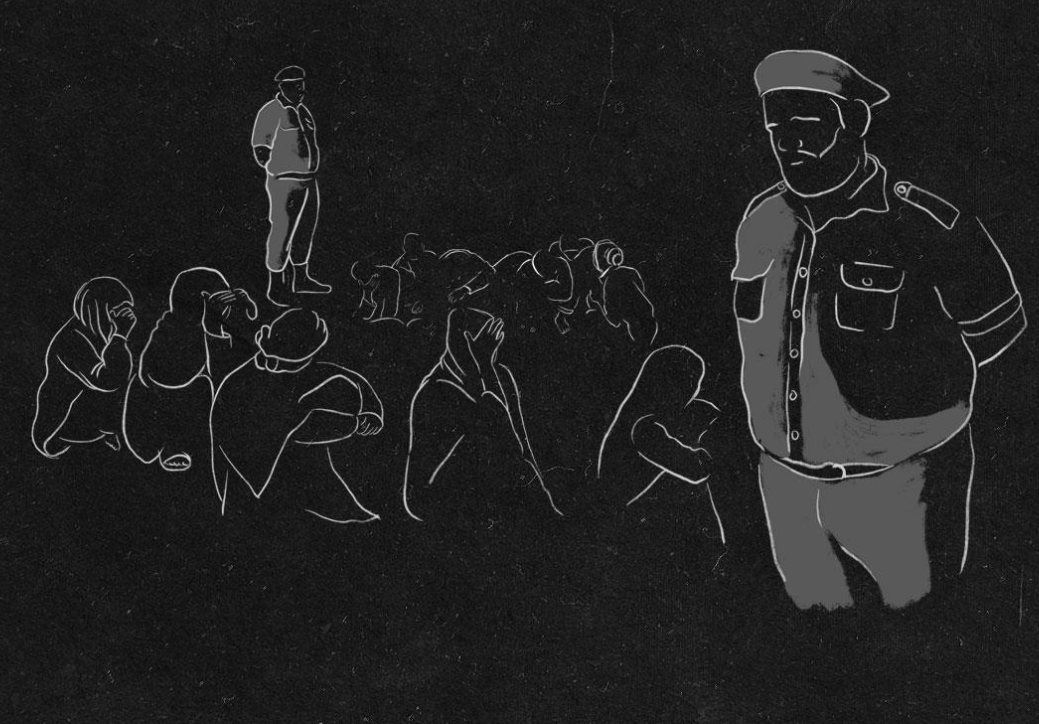

Self-harm is one of the only way detained individuals in the Italian CPR can make a − often ephemeral − stand. The only year, continues ASGI, for which we have data related to these practices is 2011. In the Turin CPR that year, there were “156 episodes of self-harm, 100 of which were due to ingestion of medicines or foreign bodies, 56 of which due to stab wounds”. Material living conditions in the centre are of course part of the problem. ASGI reports that “The living spaces reserved for the inmates include 50-square meter modules, including bathrooms, where seven people live, eat and sleep.” It then continues describing in full the conditions of life in such modules:

“Each bedroom has an en suite bathroom, which is accessed directly from the room itself. Between the bedroom and the bathroom there is no door, nor are there any dividing doors inside the bathroom to separate the two squat toilets from the rest of the room where there are two washbasins and a shower. In other words, a few meters separate the toilets from the nearest beds and there is no element of furniture, such as doors or at least curtains, to ensure a minimum of privacy to those who use the services. This state of affairs is unacceptable, unjustified and non-compliant in terms of security.”

The Permanence and Repatriation Centres are part of the militarisation of society, of this war that is fought on and with the body of an ‘other’, the migrant and the asylum seeker. This ‘other’ is constituted ad-hoc, as a containable figure, not only in the sense of a person who can be imprisoned, but of a subject who is made to take the political, epistemic and material charge of the struggles of this world that we cannot and do not want to face.

And so a dispossessed subject is created with systematic hatred, confined in very Italian Lagers, which are then also new ‘asylums’: total institutions for people who come in healthy and go out with the mockery of a letter of departure, mad, sick, tired. If they get out and don’t commit suicide first.

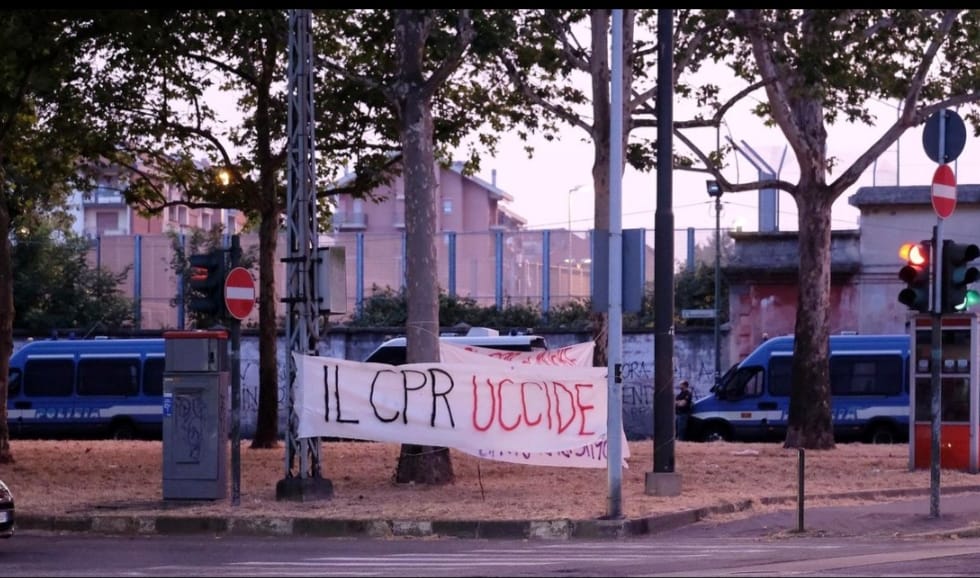

Today, a piece of important news broke: the CPR of Milan has been seized by authorities, after months in which activists have worked hard to show the conditions of life in such a space (summed up in an another excellent report by ASGI). An operator of that CPR-lager testifies:

‘Synthetically I can say that it was a real lager, not even dogs are treated like that in kennels. […] Firstly, there is widespread use of psychotropic drugs given like candy and in high dosages. During the summer it could happen that soap, although present, was not given to the inmates, so in practice showers were not taken. They were prevented from talking to the lawyers. The food was very often expired, spoiled”.

From Australia to the UK, passing now through the signed agreement between Italy and Albania, it is customary practice for Western democracies to offload migrant detention centers to third countries, and to replicate the model of the CPR away from the eyes of activists and engaged lawyers. The only possible response here is #abolition.

Here the term, following critical Black praxis, does not simply signify closure – but invokes a total overhaul of the practices through which we (Italians, in this case) legitimise our sense of home and belonging, of habitation and dwelling. As I expand upon here, what needs to be abolished is the need to constitute an ‘other’ of ‘home’ for ‘home’ to stand in the first place. It is about fighting borders and their technologies. It is about refusing the colonization of bodies and subjects. CPRs need to be closed down now, not as an arrival point, but as a departure for further, more radical struggles.

Photo: Images from the ordinance testifying to the terrible conditions at the via Corelli Cpr in Milan (il manifesto)