I was recently interviewed by Milena Belloni for the ‘HOMING‘ project run by Paolo Boccagni. In the interview we discuss homelessness, home, and radical research practice. You can read the interview at this website or below.

Interview Michele Lancione (Trento, 25th September 2018)

Milena: What does home mean to you, to your work and to your disciplinary approach?

Michele: Home is where everything starts. We have “the homeless” because our idea of home includes the possibility of being without home: you can be at home but you can also loose that home. That is what interests me about “home”. It’s impossibility. Even if home is the place where you belong, and where you have a nice life, there is always the potential to lose that. This complexity, this conundrum, is the whole point. Home is never something that is safe, that is neat and clean. It is always something that is contested within and outside; something that is lost and re-appropriated.

Milena: While you were talking I was thinking…does the condition of homelessness exist? If we think that we are never completely at home we are also never completely without home. How would you

Michele: That is very interesting. In something I recently wrote I said that homelessness does not exist. What I try to argue is that one can also be homeless at home. Even if you live on the street you have a lot of relationships of affection and care that you consider being part of home. At the same time you can be homeless even if you have a conventional home, as the threat of losing it is always there. Your house can be appropriated by a bank, your love relationship can end. Thus, you can have belonging and safety on the street, in a camp and when you have a real house you can experience the precarity of being homeless. I find very useful a concept developed by Katherine Brickell, a British geographer. She speaks of home making and home unmaking: a continuum, a conundrum.

Milena: Could you give us some ethnographic example of homing and unhoming?

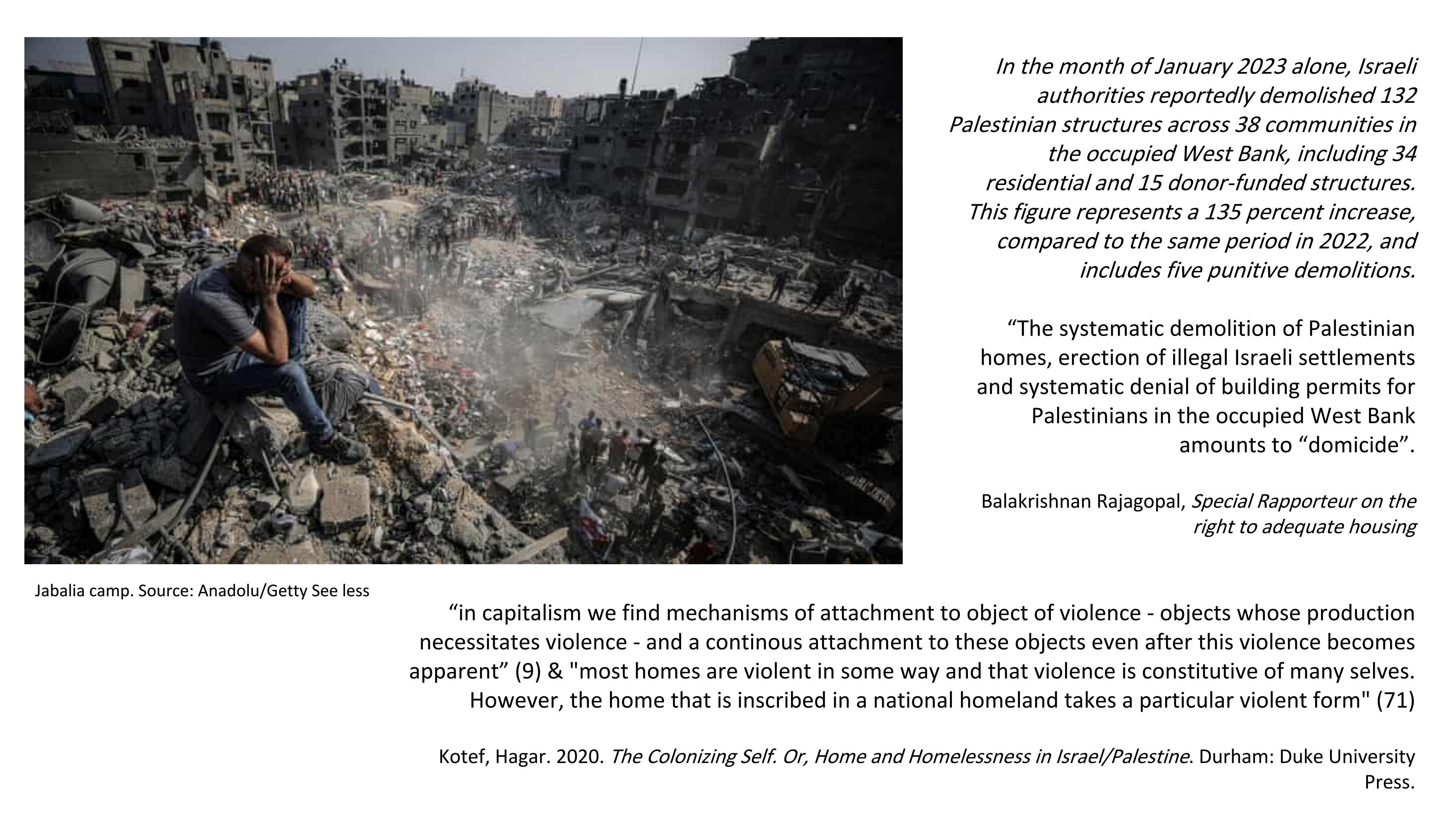

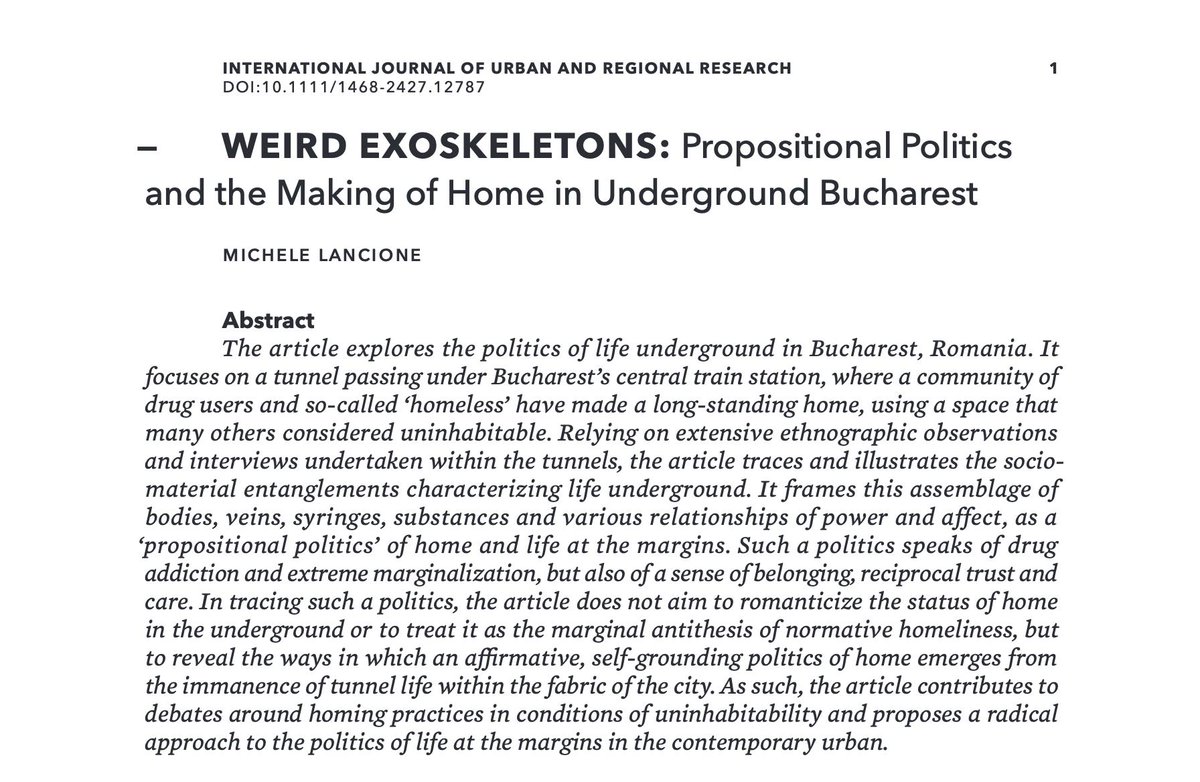

Michele: There is a lot of work on violence, domestic violence, patriarchy, which shows how you can be at home while not feeling at home. My work however is about the opposite: how can people who do not have at home feel at-home? I worked with drug users and homeless people living underground in the canal in front of the main train station in Bucharest. This story is widely known as it has been extensively portrayed by the media and academic world. The standard message you can get out of these portrayals is that these people are resilient. But when you live with them you realise that there is much more to it. People living underground have a community, are not just ‘resilient’. They make life: they do not just ‘get going’, or ‘survive’. This is a life characterised by caring relationships and by an economy – monetary and affective – to support the underground; in fact, in a way this economy is not so different from what you have above ground. Certainly it is a weird arrangement for many reasons. But it works. And when they were eventually evicted from the underground by Romanian authorities, those people were not able to replicate their life outside. Many got jailed, others dispersed. They lost the capacity to be alive, to construct their ‘weird life’… Many died. This is the result of the rejection by the institutions of the possibility of life underground. The institution – that is, the institutional accepted norm – rejected the possibility that you can function even if you are junky and you live underground. The point here is not arguing that homeless people should be maintained in the underground, but that we need a politics able to appreciate first, and embrace second, the proposition of life underground: a lively arrangement was created down there, which does not work (it stops to live) when it is captured into normative understandings of home, of belonging and of acceptability.

Milena: Is there an alternative to keeping them underground and also to the forcing them into shelters which they do not perceive as safe?

Michele: Yes, I think there is. Policies of harm reduction would be important in these contexts. Tthis means that I am not trying to stop you from using drugs, or to destroy your community, to institutionalise you. All I am doing – as the authority – it is to make sure that you are not harming others and yourself, by giving you cleaning syringes and providing you with medical assistance. Life underground is very hard, often without heating, without electricity. But we can reduce the harm of that life in there – or in other similar context – without destroying them. Their relations, their belonging, their care and their economy could be maintained through ‘soft’ interventions, which would not rob vulnerable communities of their capacity of being together. Of being close to each other… Evicting and imprisoning and controlling castrate that opportunity: it silences it.

Milena: What are the most relevant empirical and methodological challenges that you identify in researching home and migration?

Michele: Maybe not about migration so much, as it is not something that I have been looking at. In relation of home, the biggest challenge for me in the last years is how to make research in a way that is meaningful for the people you are researching. I mean it in a profound way. Not simply in terms of co-production of the research goal. But in terms of constituting a shared political ground where the research becomes just a tool amongst other to intervene on the social. This is not per se a methodological challenge but rather an ethical issue…it becomes methodological though. Because you can say from ethical point of view that you want to coproduce the research with your research participants and stuff like that, but then, how do you do it, really? Can a research be co-produced, if sometime (actually, the vast majority of times) is not research what is needed? The first concern of the person in front of you is not to answer your questions, is actually to change the clothes of her child because she needs to go to school. The challenge thereofre is to displace our own research priorities and carefully think about the encounter. For that you need to be humble and realise that for a while you may not do your research because at that point it is more important for the relationships that you are having to engage in forms of collective solidarity and help. We should allocate time in our project to do that kind of work. If that time is not there, then the project is always going to be one-way. Always ‘extractive’, no matter what. If, on the contrary, you are able to meet the other in a meaningful way – keeping in mind all structural power unbalances – then not only you will establish a meaningful relationship but also your research priorities will change. Here the point is to be open to change. If you start with one idea you should never be able to finish with that same idea, that same project, that same proposition. Actually I think that you get stuck with an idea and you try to enforce that idea on your fieldwork then there is something wrong about your fieldwork. If you do ethnography in the right way – the crisscrossed way, the minor way – then you will see that people will take you somewhere else. They do. They always do! It’s a big challenge because at the end of the day you also need to give something back to those who have funded the project. But with experience you know how to deal with these issues. The most important thing for me is to follow the fieldwork, not to please the founder or the institutional arrangement.

And then, of course, there is also an added element of complexity. The representation of the encounter. How do you represent this encounter is a way that is truthful to its complexity and meaningful for you and for those you have worked with? The key question is how can they appropriate and use that representation that you create thought your work with them. Here there is a slight difference between giving something back and working toward something that can be appropriated, modified, trashed, changed, used again. Giving something back is a photo voice exhibition. I am thriving for something more radical. Let’s try to find something that is open enough so that once you are not there anymore, communities can see value in it, use it, dismantle it, reassemble. I think that if you want to be a good ethnographer you should at least try to orient your work in that direction.

Milena: Can you give us some example?

Michele: My PhD research was done at Durham, UK, with a fieldwork around homelessness in Turin, Italy. The dilemma was I wanted “to give something back” to my interlocutors, but my PhD was in English. I needed something in Italian and accessible. So I came up with this idea of writing a novel, an ethnographic novel, and to make it as collaborative as possible. I was giving my writings to the homeless men I was working with. These notes and accounts where about their life, and life on the street in Turin. They were giving me feedback and time after time I constructed this book, ‘Il Numero 1’, which is actually a composite book. There is an introduction by one of my homeless friends, there is an ethnographic novel, and then there is a political essay at the end. There are also 22 illustrations in the book by Eleonora Mignoli. We published the book and then we presented it in Turin with my homeless friends and so on. The book was published by an anarchist press and it still travels, but I was never able to continue the engagement on the ground, in Turin. So in a sense it was helpful to ‘give something back’ but not successful in constructing, on in working with, a radical solidarity.

A second example, this time in Romania. I encountered this community of evicted Roma people and I started to work with them as an activist, because my research was with the drug users. Just to keep it short, there were a number of collective actions and involvements, mosty through a group of which I am now part, called the Common Front For the Right to Housing. Protests, petitions, solidarity on the street and more. Including a blog that I’ve set up, where Nicoleta, a powerful woman from the community, explained why they decided to occupy the pavements in front of their home for almost 2 years, to protest against the eviction and fight for their right to housing. During my involvement with the community I also made a lot of videos – interviews and everyday life – and at the end we decided that there was scope to assemble this material into a documentary. 72 minutes telling a story of racialized dispossession, post-socialist housing privatization and the making of resistance. The interesting thing about this documentary is the following. It did not stop there – as an on-line thing for academics or film-makers. In the past two years we (as FCDL) are using that documentary to do workshops with communities who are facing eviction or experienced it, and we are also presenting it in a number of context where evictions are lived and felt (like squats). We did this in a number of spaces across Europe, including squats in Rome (like Metropoliz). The documentary becomes an excuse to sit together, get inspired and discuss about common struggles. It is not just a film, but an excuse to create solidarity.

Milena: So the difference between your first work and your last documentary is that the first one could not be appropriated but the second one instead is becoming a tool for political actions.

Michele: It can be used by others. The novel is a finished product. It is there. You can buy and that is it. Why the documentary is a moment in a series of things. First the blog then the documentary then with Nicoletta we are now writing a book: all things that are part of a collective process, occupied by different people at different times, but alive and kicking. For the book we just got an award by an American foundation, Antipode (eg. The Scholar-Activist Award). The “Diary of resistance” by Nicoletta will be in Romanian but we will also translate it into English, to continue to travel and create trans-national solidarities. It is a continuum of projects which are not necessarily academic but they speak to the public that you are working with. And the reason why I am able to do all this it is because I am collaborating with people who are doing what they are doing. They have their hand into life and they keep those tight in there! It is really on the same level. When I did the first cut of my movie, they destroyed it. I showed them and they said “change everything”. But that is fine, it couldn’t be otherwise. It is because of Veda, Iox, Misa, Carolina, Nico and many others that this thing is possible and research becomes just my way to get into the flux. They have theirs. What we share is the politics, the orientation.

Milena: Our project is framed around processes of home-making in relation to contemporary migrant trajectories. What do you think this approach can add to the field of migration and home studies?

Michele: I am not entirely familiar with migrant studies. But I know the work of Paolo and his papers. I think that what you are trying to do is super-important and meaningful because you are trying to add complexity to the idea of migration as a set of issues that is not completely detached from home. You are saying there is a continuity between losing your home and finding, or not finding, another home. The matter is the struggle that comes to the fore in this process. The complexity is what I like about the project. The cost is that you are not going to provide an easy answer. It is not going to provide one theory that explains everything and this is the real contribution if the project: to do not reduce things to neat structure, to a fix picture.

Milena: What kind of strategies would you suggest for studying home-making practices, considering that privacy is sensitive point? How did you deal with that gesture of censorship, which came from the mouth of those you were giving voice to in your writing? Do you think that some of our ethnography on the nexus home-migration might stir similar rejection from our research participants, either during fieldwork or at the time of results publication?

Michele: It depends on how you do the research. Of course people may say something to you in an interview after signing a consent forma and after they may be pissed off about the way you represent that thing. Here again I think that ethnography can do something that another epistemologies are not able to do. If you are serious about the encounter it means that you are leaving the window open to dialogue and that implies the possibility of disappointing people and of getting criticised, attacked and rejected. That’s all fine and healthy. When I published the novel on homeless people in Turin, there was this homeless woman that posted on my Facebook wall that she did not feel represented. I knew this was going to happen as I knew that I did not represent women enough. I told her. You are right. We just had a conversation, the problem was not gone. That woman is still not represented. But thanks to that encounter and confrontation I learned a lot about the limits and nuances of my research. And I know that she got something out of that too. The trick in here is to understand that the writing is not the final thing in your project: it is just the part of long term relationship that you are entering with the community you work with. To do ethnography means to continue having relationships with the people you are working with and those are sometime just too much to bear, but that’s the way it is. Relationships affects you and you affect them through what you do, what you write, and that has its onw life that intersect with yours, and keep on intersecting…

Milena: Do you still have relationship with all the people you worked with? In terms of personal engagement. You cannot become friends with everyone. You don’t like everyone…

Michele: I don t meant that we have to become friends with everyone, but that through a careful ethnography you are able to establish relationships that are open to dialogue, even to confrontation, even with the ones you don’t like. That is the beauty of it. It is not about surrounding yourself only with the one you like, but using the ethnography (and the engaged political orientation of which I’ve said) to funnel life, to let it emerge and pass through (through you, your writings, and collective endeavours). This, again, is not about having to come to an agreement with everyone. There is a lot of productive energy into having disagreement and conflict, as much as there is into agreeing and hugging. In my work I just try to create the conditions for these things to come through, and to stay true, in order to fight against discrimination and institutional normativity. It’s still a work in progress.

Thank you!

Publications: www.michelelancione.eu

Documentary film: www.ainceputploaia.com