A inceput ploaia – Trailer (ENG) from A Community Productions on Vimeo.

In what follows I want to offer my perspective on how I came about making a 72 minutes film on forced evictions in Bucharest, Romania, which is called ‘A început ploaia’ (‘It started raining’). The film is about evictions and displacement in the Romanian capital and, in particular, about the story of a community of Roma people that fought against their displacement with uncanny and inspiring endurance. I have written about the interrelation of housing, race and capital in a short piece in Open Democracy and, more recently, I have reasoned around the possibility of sustaining grass-roots forms of resistance like the one represented in the film in a paper published in the pages of Society and Space (Revitalising the uncanny: Challenging inertia in the struggle against forced evictions).

This text is a more personal and auto-ethnographical narrative of how I encountered Bucharest, its people, struggles and forms of resistance. This text is an attempt at showing the fragility of urban ethnography; at rendering visible the possibilities of active engagement; and at giving justice to the wonderful people that made the film and many other things possible, starting of course with the community of Vulturilor 50, from which I learned – and I am still learning – a very good deal.

Background

Since my first visit to the country – in 2003, for my Erasmus – I have always had a special attraction to Romania and to Bucharest in particular. The city is simply alive in a sense that many other cities are not – full of its contradictions, grey blocks, broken sidewalks but also beautiful mingling in open and closed markets, vast public parks, improbable decadent restaurant serving you amazing mamaliga, salata de vinete, caşcaval pane si murături & more. This is possibly why, when I was writing a post-doc application while living in Sydney (Australia), I decided to make it about Bucharest and its ‘margins’. Although Sydney and UTS were a rewarding break from my previous work around homelessness in Turin, Italy (see for instance this, this and that), at the time I also felt the need to come back to Europe and to embark, once again, in a long-term ethnographic project. Luckily enough the people at the Urban Studies Foundation (USF) believed in that project, financed it, and allowed for my return to the UK (where I ended up working in Cambridge with my PhD supervisor, mentor and source of constant inspiration, Ash Amin). This was the beginning of 2014. Six months later I was in Bucharest, ready to start my fieldwork around a ‘problematic’ neighbourhood in the city, Ferentari. That fieldwork never took place, at least not in the way I was expecting it to.

Accordingly to my Post-Doc project – which I probably wrote in one of those moments of over-enthusiasm about life, possibility and strength – I was aiming at doing three case studies, in three different cities: Rome, London and Bucharest. The case studies had to be of extreme marginalisation in specific areas of those cities, with the aim to construct alternative forms of understanding and knowledge about (and with) those spaces and people. In the end, I became entangled with Bucharest so much that I never moved from there, continuously living in the city for a year, and constantly coming back thereafter. During this time I changed research project a dozen times, opening up and closing down possibilities and ideas, while receiving an incredible support from Ash and Chris Philo, head of the USF, without whom this work wouldn’t have been possible.

During the year in Bucharest my main ethnographic work was focused on street level drug use and services for users across the city, with particular reference to a couple of streets in Ferentari and the underground canals of Gara de Nord (on the latter, look at the wonderful work of my friend Massimo Branca, now published in a book with an intro by myself). Eventually, I will publish about that research and I will try to give it the justice it deserves. The reason why I wasn’t able to do so until now (mid-2017) it’s simply that, in September 2014, only after a month living in Bucharest, I received a phone call by another good friend – who at the time was just a name in my list of people to contact: Marian Ursan, head of a local NGO called Carusel. The conversation was more or less as follows.

Me: Hi Marian, it’s Michele, the researcher….

Marian: Hi Michele. Yes. I know. We have to meet. Where are you now?

Me: At Unirii, near the main library… why?

Marian: Bine. Come in Vulturilor. I am going there. An eviction took place and I am going there, people are all over the place.

Me: But are you sure, what if…

Marian: I’ll see you there in half an hour, pa!

At the time I didn’t even know where Vulturilor was and I had no idea of what Marian was talking about. I turned my GPS on, looked at the map and, seeing that the place wasn’t too far from where I was… I decided to give it a go.

Eviction

That day of September 2014 I stumbled across the aftermath of a massive eviction in which 20 families (around 100 individuals) had been thrown out onto the street after having lived for many years — for some up to 20 — in the house they were now only able to see from the pavement. The first thing I did was to help people moving stuff, to hold this-and-pass-that, to play for a few second with a kid before turning and starting to do something else. In those first moments I was lost: I did not know anyone there and no-one knew me. I had no purpose and no understanding of what was going on. Almost as an instinct, without knowing what else I could have possibly done, I picked up my camera and I started taking stills of those moments. I wasn’t the only one. Journalists and photographers were a constant presence during those first days, alongside a number of activists, NGOs’ staff and volunteers, as well as the occasional politicians. Most of them were gone after a few days. The people of Vulturilor however kept, for the most part, on staying on the street. They did not want to move, unless the Primarie (municipality) was able to offer them a viable alternative to their eviction and consequential homelessness.

Without entering into details, which are instead explored in the film, it is worth stating that those people were (and still are!) entitled to social housing by Romanian legislation. The provision of social housing is, however, almost completely absent in Romania, counting for less than 1.5% of the total housing stock. Moreover, as it has been well documented, the allocation of this stock follows corrupted paths, which for the most do not include Roma ethnics like the people of Vulturilor (for an overview of this, read Irina Zamfirescu’s excellent paper or look for the works of Liviu Chelcea. A provocative but truthful account of housing racisms in Romania, which I wrote for Open Democracy, can be also found here.

The evicted people of Vulturilor – about 70 in the first few months after the eviction – decided to dwell on the street to protest against forced displacement and to fight for their housing right. This came as a surprise to many, including long-term activists and experienced social workers, as the general understanding was that, in Romania, Roma people simply do not protest with such virulence and visibility. Although, as confirmed by Amnesty International, they are ‘disproportionately affected’ when it comes to forced evictions, Roma ethnics tend to find alternative accommodations within their extended families and friends. They are, after all, used to be displaced and to being pushed at the margins in Romania (but also everywhere else in Europe). The case of Vulturilor was, however, different: the evicted, perhaps strong of their number, decided to stay, protest, and make their voice heard. The power of such a choice affected a number of activists – such as the one belonging to the Frontul Comun Pentru Drept la Locuire (FCDL – Common Front for Housing Rights) – and NGOs – such as Carusel: a community of solidarity was immediately created. Tents were built, food cooked and distributed, clothes collected and donated, and moral support given around the camp’s fire every night.

During those days (from September to mid-October 2014) I still had no idea of why I was going to Vulturilor. I simply kept going there, every late afternoon, accompanying Marian and the other amazing people from Carusel (like Ana, Cristina, Andreea, Iolanda, Ion, Roxana and my brother Bogdan), helping them with the distribution of food or second hand clothes. I felt, in a sense, that I was there as an activists… but of a strange kind. I was looking up to some of the powerful local activists (like Veda, Ioana, Victor or Irina) carrying on the burden of helping people with concrete actions – such as completing the dossier for social housing – and I was finding myself almost out-of-place. I was attracted to the people of Vulturilor, their story and most of all, to their uncanny resistance. But why was I there? Why keep on going there? In the end, no one really needed me or my camera, for what mattered.

Entanglement

It was a Saturday, the 25th October 2014. I remember that I woke up in my flat in the Southern part of Bucharest thinking, shit! Rich and fluffy snowflakes were falling outside my window, for the joy of kids and the discomfort of many others including, in particular of course, the ones living in the provisional tents on the sidewalks of Vulturilor. I dressed, took my bag and rushed into a taxi to get there as soon as possible. I still remember that in the journey to Vulturilor I asked myself: and now, what would I do? Why am I going? What can I offer? When I arrived, the people were standing around the fire, trying to warm themselves up, while the tents were for the most part collapsed, leaving everything inside cold, wet and unusable.

Despite all that mess, the community was calm, and so were the activists. They had, in a sense, nothing left to worry about beside their own body. Without having much else to offer, I provided accommodation at my flat to whom needed it until the weather turned better (the owner of the flat, a Roma himself, eventually forced me out of the property because of this action, arguing that I wasn’t supposed to host ‘such people’). It was decided that I would take care of a family with a substantial number of minors – four. Two taxis brought us back home, things were arranged, and while the parents rested and the younger kids played, myself and their older sister cooked an Italian pasta that – to say the truth – it wasn’t very well received: matter of taste!

From that moment on, my relationship with the community became tighter and more sophisticated. In a sense, I guess, they were now able to locate me as someone caring about them, not only because of my daily bodily presence around the camp, but also because of small, concrete acts of care. Beside hosting some of them when needed, this ‘caring about’ was made of simple gestures, including chatting, offering a word of support, printing and distributing pictures, or simply hanging around and make everyone laugh with my broken Romanian. It was through those small acts and gestures, those bodily transpositions and assemblages, that I became increasingly entangled with the everyday life of people in Vulturilor. Even if I was going there mostly in the evenings only – since during the day I was still researching about drugs in other areas of the city – the assemblage of that street, those people, the fire, shacks, documents, wood planks, cigarettes, coffees and my body… gradually became a quintessential part of my life in Bucharest.

That assemblage was however still lacking a clear political scope. There was, of course, a micropolitics of care going on… But just that, I believe, wouldn’t have been enough for me to carry on my involvement with the community. Fortunately, one day of November 2014 something powerful happened. Nicoleta, a young working mother among the most vocal against the eviction, approached me and said she wanted to talk. I can’t honestly remember why… but we ended up talking in the back of her father’s taxi, while her brother was driving it to bring something to their cousin, somewhere else in the city (serendipitous Bucharest!). More or less, this is what she told me.

Nicoleta: You took many pictures, from the beginning, right?

Me: Yes, I have a lot!

Nicoleta: And you have also video as well?

Me: Some, but I can make more.

Nicoleta: Here things are not moving. All it’s the same. And we need people to know. We need the media to know. We need to create some noise, or nothing will change!

Me: I agree. What do you have in mind Nico?

Nicoleta: I don’t know. Why don’t you put this pictures online? Why don’t you send them to the media, the TV?

Me: Because they won’t publish them. They are not interested in this stuff.

Nicoleta: So let’s do a Facebook page! Let’s do a page where we write about life here and you put your pictures, and we’ll tell everyone how we are living!

Me: This is a great idea! Let’s do a blog.

Nicoleta: Un jurnal?

Me: Da, un jurnal!

The first blog post was published just a few days later at www.jurnaldinvulturilor50.org, where it can still be read. Thanks to that idea, Nicoleta gave to my presence and my activism a scope that I wasn’t able to find on my own. In a sense, she made me politically relevant. From that moment on we worked together, up to the very end of 2015, producing more than a year and an half of posts featuring Nicoleta’s writing, which was representative of the community’s experiences of resistance and frustration toward the authorities. It is because of the blog that, in the end, I became more systematic in my recollection of visual material. Parts of what later entered into the film was indeed originally purposely created for that platform, like this clip showing the indifference of the Major of Vulturilor’s sector, Mr Robert Negoiță, to the situation.

Leaving

I kept on going to Vulturilor almost daily, up to the time in which I had to leave Romania and move back to the UK (June 2015). During those months I made numerous recordings, which for the most part did not make their cut into the documentary (in total, about 700 short clips). Before leaving I organised all the video that were published on the blog on a timeline, burned that into a number of DVDs, and distributed those to the community members, which at the time counted about 40-50 individuals, still living on the same sidewalk where I found them almost a year before.

Leaving wasn’t easy. Although I had nice memories and lots of new friends, in June 2015 I left Bucharest exhausted – by its streets, buildings, cigarettes, food. I couldn’t bear Ferentari anymore, nor the harm reduction centre where I had spent ten consecutive months; I couldn’t afford to think, even remotely, at the underground canals of Gara de Nord; and I wasn’t motivated at all to keep on going to Vulturilor. Toward the end my visits became shorter, less meaningful, almost out of a sense of duty more than care. Although my friends made me feel good, throwing good parties and telling me that they were going to miss me, I knew that I hadn’t achieved enough during those months. What I was leaving behind? What kind of impact did I have in the live of the people I encountered?

During the summer, back in my shared flat in London, I reviewed some of the videos but I soon realised that I did not have the strength to approach them systematically. As it always happens to me after a long fieldwork, I was tired, demotivated and fundamentally depressed about what I had been doing in Romania for all that time. During that summer only my partner’s advice kept me from deleting everything and trowing all that ‘garbage’ – this is how I was referring to my videos and pictures at the time – away. It is mainly thanks to Eleonora – and her cinematic experience – if later on, during the Autumn, I started to reconsider that video material as something interesting and potentially meaningful.

While trying to organise them into a coherent database (something that, by the way, never happened!) the idea of the documentary came about. It seemed to me that those videos, if properly arranged, could have spoken back to Nicoleta’s original request: to let others hear their story; to give to the community’s fight for housing an even stronger voice. In other words, those videos could become a way to translate the experience of all those months in Vulturilor into something meaningful and relevant not only for me, but also for the people I encountered and spent time with. This is a peculiar kind of translation which an academic paper cannot achieve. As my experience of writing an ethnographic novel for my homeless friends in Turin back in 2011 taught me, creative methods can allow for empowering experiences and impact (I wrote about that experience in here). That is why, in the end, I convinced myself that a documentary was needed.

In November 2015 I went back to Bucharest and I conducted, in four days, a number of interviews with a number of key experts on the country’s housing history and related struggles (thanks in particular to Liviu, Mircea, Petre and Mihaela for their time!). These interviews allowed me to complete the material I already had and to move a step closer to the production of the film.

Co-producing

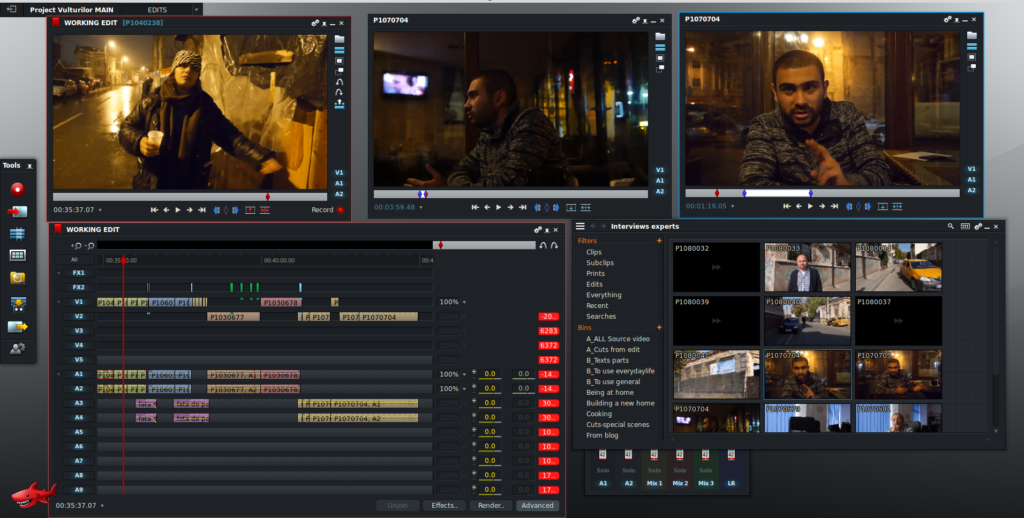

I started editing the film in the first days of May 2016, roughly six months later than I was expecting to do. This was mainly related to the fact that in that time I had to pass through the laborious process of securing a permanent academic job – something of which I will eventually say something elsewhere! Without having any previous experience of editing – but also without having the proper hardware – I ended up largely under-estimating the task. The first cut of the film took almost three very hard full weeks of work, including weekends and most of the evenings.

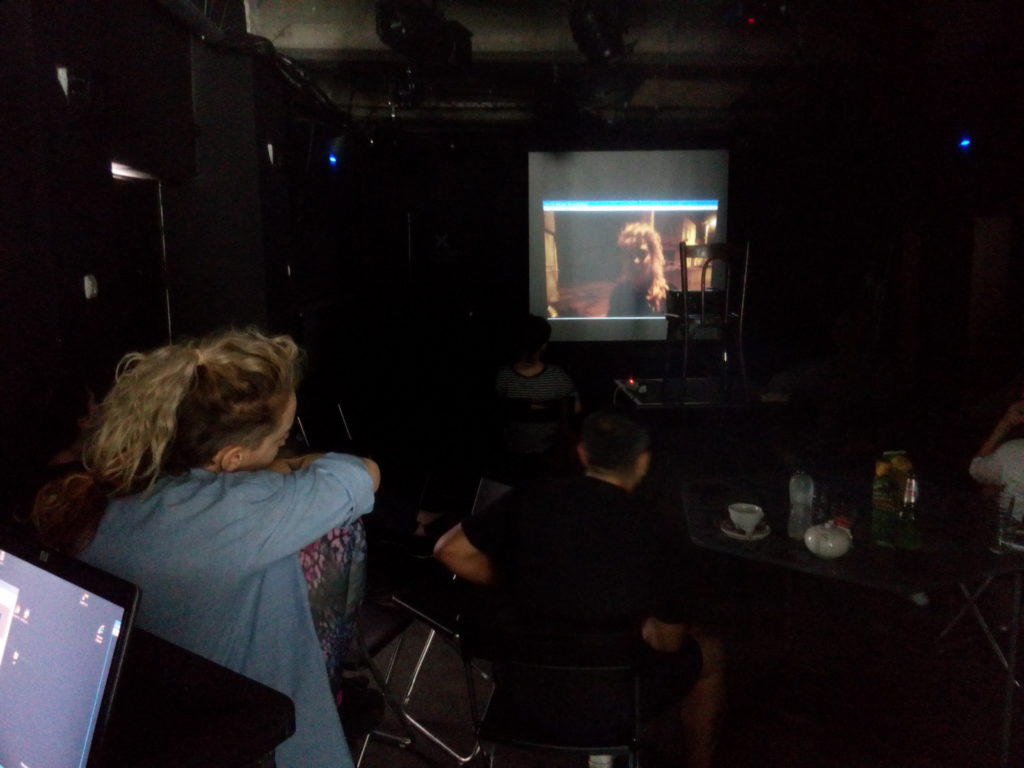

At the end of May 2016 the first cut was ready but I didn’t do anything with it. Only in mid-June I decided to export everything, to go back to Bucharest and to organise a workshop with as many community members as possible in order to receive insights and feedbacks from them. Irina – a scholar-activist working at Active Watch – and Veda – a key activist from the FCDL – helped in the organisation of the workshop, which took place in Macaz, a social centre in Bucharest in mid June 2016.

The workshop was a powerful experience. There was a good number of community members (about three of the remaining five families still living on the street at the time) as well as a number of activists and scholars. I was terribly stressed, not knowing if the extreme low quality of my cut and of the video would have been good enough for the audience to enjoy. Most of all, I wasn’t entirely sure about the film as a whole: did I produce something representative of the community’s struggle? Did I get the nuanced Romanian housing history right? Did I allow for complex issues to breathe or did I over-impose my own Western perspective on them?

The discussion that followed radically re-shaped the structure and, to a certain extent, the content of the film. If ‘A început ploaia’ is what it is today – a feature documentary of 72 minutes, with a coherent beginning and an hopefully meaningful end – it is also because of the feedback that I received that day in Bucharest. People from the community asked me to cut things, to move scenes and to allow for their experience to be more represented in the film; activists challenged me on the framing I gave to the documentary, providing a strong post-colonial critique of some of my choices (for which I deeply thank Veda); while scholars allowed me to better understand some aspects that I had over-simplified. Everyone agreed, moreover, that I had to present myself in the documentary – something that I did not do in the first cut, which however became an important feature of the final version (for this comment, I thank Charlotte, Alina, Robert and Irina Z. in particular).

In the end, I left Bucharest energized but also scared: now I had to make the changes and I had to finish the project. I created an expectation that I had to meet.

Post-producing

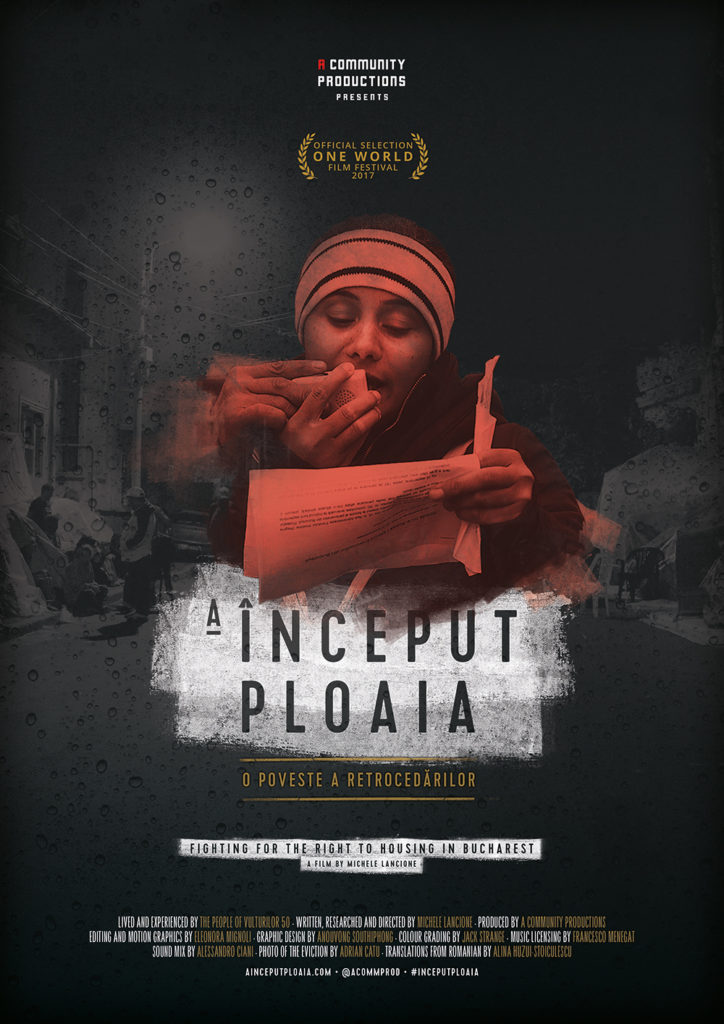

The post-production of a film is a huge endeavour, especially if one has no budget and all work has to be done either in-house or through friends. The post-production of ‘A început ploaia’, which involved editing, colour grading, sound mixing and creating the animations featured in the documentary, started in mid-November 2016 and it was over by the beginning of February 2017. A lot of work was put into its making, in particular by a bunch of amazing individuals: my partner Eleonora (which edited the whole thing, animated the content and collaborated at the colour grading), my friend Vong (who did an amazing work in creating the graphics, the website and the poster of the film), and my two old pals Francesco (who cared about music licensing) and Alessandro (who mixed the audio). All of these people virtually worked for free, just believing in the project. A lot of help was also given by three Romanian friends: Alina (who translated everything in English), Irina Z. (who provided constant support and was able to record Nicoleta’s last contribution to the film) and Irina G. (who was of incredible help for the music). Eleonora, in particular, deserves further appraisal, for being able to cope with an academic-husband who is also, at least momentarily, a director: the worse combination ever. The film taught us a lot and I am grateful for having had her on-board.

‘A început ploaia’ is the product of all of these people as much as it is mine. I take responsibility for it, but they should take the credit for making it possible.

Releasing

‘A început ploaia’ was presented officially at the One World Film Festival in Bucharest, 13-19 March 2017 (with a preview in London on the 24th of February, 2017, at UCL thanks to Pushpa Arabindoo and Claire Dwyer). The film was well received by the general public, with interviews and the likes featured in a number of outlets in Romania (see for instance here, while more are under production and will come in the second half of the year).

Most importantly, the key moment for me was a private screening and party organised by Veda and the activist of FCDL at Macaz, for the people of Vulturilor, Rahova Uranus and the ones involved in the resistance of those community against evictions and displacement. The speech that Nicoleta gave that day after the screening; the tears of her father; the vivid attention of other members of the community and the engagement, at all level, of members of the public (activists, scholars, artists and more)… The fact that people came to me telling me that they felt represented by it and also proud of how it was, of how they were represented in it… That atmosphere of solidarity was the best return I could ever get from this film and the best moment in its making.

What is yet to come

The future of this project is still, for the most part, unknown. I hope for it to become an active testament of the fight for housing in Bucharest – one that will be used by activists, evicted people and researchers to strengthen their resistance to displacement and to fight continuous harassment. In order to work toward this direction, I would like for the film to be seen by three kind of audiences. Firstly, I am organising screenings for activists in different European cities. The idea is to travel with Veda and Nicoleta to discuss the film and its story of resistance across the continent, in order to create new solidarities or strengthen existing ones (for instance the ones already in place through the European Action Coalition for the Right to Housing and to the City). Groups in Barcelona, Berlin, Budapest, Rome and more are responding and activities will be organise throughout the summer and fall 2017.

Secondly, I want the film to travel in Film Festivals to engage with a community of professionals who may be interested in co-producing similar works in the future. In this regard, I have submitted the film to a number of international Festivals and I hope for it to be screened in a number of venues across the whole 2017. Similarly, I would also like for it to be broadcast on TV, especially in Romania, to stimulate a debate around the racialisation of housing and the right to the city that is much needed in the country. Giving the political nature of the documentary this may be very hard to achieve.

Lastly, I would like for my fellow colleagues in the academy to watch the documentary and to discuss its activist visual-methodology. Some colleagues have been incredibly supportive (like the one sittings in EPD’s board, or the friend in the Relational-Poverty Network in the US); others have been scornful of the possibilities of being an ethnographer, a scholar and also a film-maker. In any case, screenings have been organised in a number of international conferences (AAG 2017, RGS-IBG 2017 and RC21 2017) and I am always open to the possibility of seminars and workshops. The film is, to me, an open tool to be used, debated and mobilised in order to work toward its original inspiration, which came from the people of Vulturilor in Bucharest: to fight against displacement and for the right to housing for everyone, in every city.

Dates and locations of future screening will be publicised on Facebook and on the film’s website. If you are interested in organising an activist screening and/or a debate, an academic seminar, or if you simply have ideas and projects to share, please contact us at info@acommunityproductions.com.

Update

In the summer 2018 we have been awarded the Antipode Scholar-Activist award, which will allow us to continue the work with Nicoleta and the community. We will produce a book and a guide against forced evictions in Romanian and English. All info here.

Additional readings

Some background readings related to the history of the restitution law and evictions against Roma people in Romania include:

– Amnesty International, 2013. Pushed to the margins. Five stories of Roma forced evictions in Romania, London. Available at: https://www.amnesty.org/en/documents/document/?indexNumber=eur39/003/2013&language=en.

– Amnesty International, 2011. Mind the legal gap. Roma and the right to housing in Romania., London. Available at: https://www.amnesty.org/en/documents/EUR39/004/2011/en/.

– Chelcea, L., 2003. Ancestors, Domestic Groups, and the Socialist State: Housing Nationalization and Restitution in Romania. Comparative Studies in Society and History, 45(4), pp.714–740.

– Chelcea, L., 2006. Marginal Groups in Central Places: Gentrification, Property Rights and Post- Socialist Primitive Accumulation (Bucharest, Romania). In G. Enyedi & Z. Kovács, eds. Social changes and social sustainability in historical urban centres: the case of Central Europe. Pecs: Centre for Regional Studies of Hungarian Academy of Science, pp. 127–146.

– Lancione, M., 2015. Eviction and Housing Racism in Bucharest. Open Democracy. Available at https://www.opendemocracy.net/can-europe-make-it/michele-lancione/eviction-and-housing-racism-in-bucharest

– Lancione, M. (2017). Revitalising the Uncanny. Challenging Inertia in the struggle against forced evictions. Environment and Planning D: Society and Space

– Rughinis, A.C., 2004. Social Housing and Roma Residents in Romania, Budapest: Central European University. Center for Policy Studies.

– Stan, L., 1995. Romanian privatization: Assessment of the first five years. Communist and Post-Communist Studies, 28(4), pp.427–435.

– Zamfirescu, I.M., 2015. Housing eviction, displacement and the missing social housing of Bucharest. Calitatea Vietii, 26(2), pp.140–154.

Special thanks

The story I told in this post wouldn’t have been possible without the help of a number of amazing people. I am listing just a few of them here, but there are more, and there will be more, to be thanked for their precious support, understanding and work! Thanks to: The people of Vulturilor 50; The people of Rahova-Uranus; Eleonora Mignoli; Nicoleta Visan; Veda Popovici; Irina Zamfirescu; Irina Georgescu; Anouvong Southiphong; Francesco Menegat; Alessandro Ciani; Charlotte Kuhlbrandt; Alina Huzui-Stoiculescu; Robert Stoiculescu; Marina Ursan & all the ones at Carusel; Bogdan Suciu & Diana; Liviu Chelcea; Mircea Toma; Petre-Florin Manole; Catalin Berescu; Adrian Catu; Future Nuggets; Travka and The Urban Studies Foundation.