I am grateful to the WOZ (DieWochenzeitung) and to Raphael Albisser for giving me space on their pages to express some ideas on urbanity, radical housing struggles and the meaning of academic work.

You can find the interview, in German, here: https://www.woz.ch/-c857

Below I am providing an un-edited automatic English translation of the piece.

Credit for the photo of the actual copy of the magazine above: David Kaufmann

AUTOMATIC ENGLISH TRANSLATION

“When it comes to housing, it quickly becomes existential”.

When people in the world’s urban centres resist displacement, they are fighting for much more than a roof over their heads. Understanding the radical quality of their resistance also requires radical research, says Turin geography professor Michele Lancione.

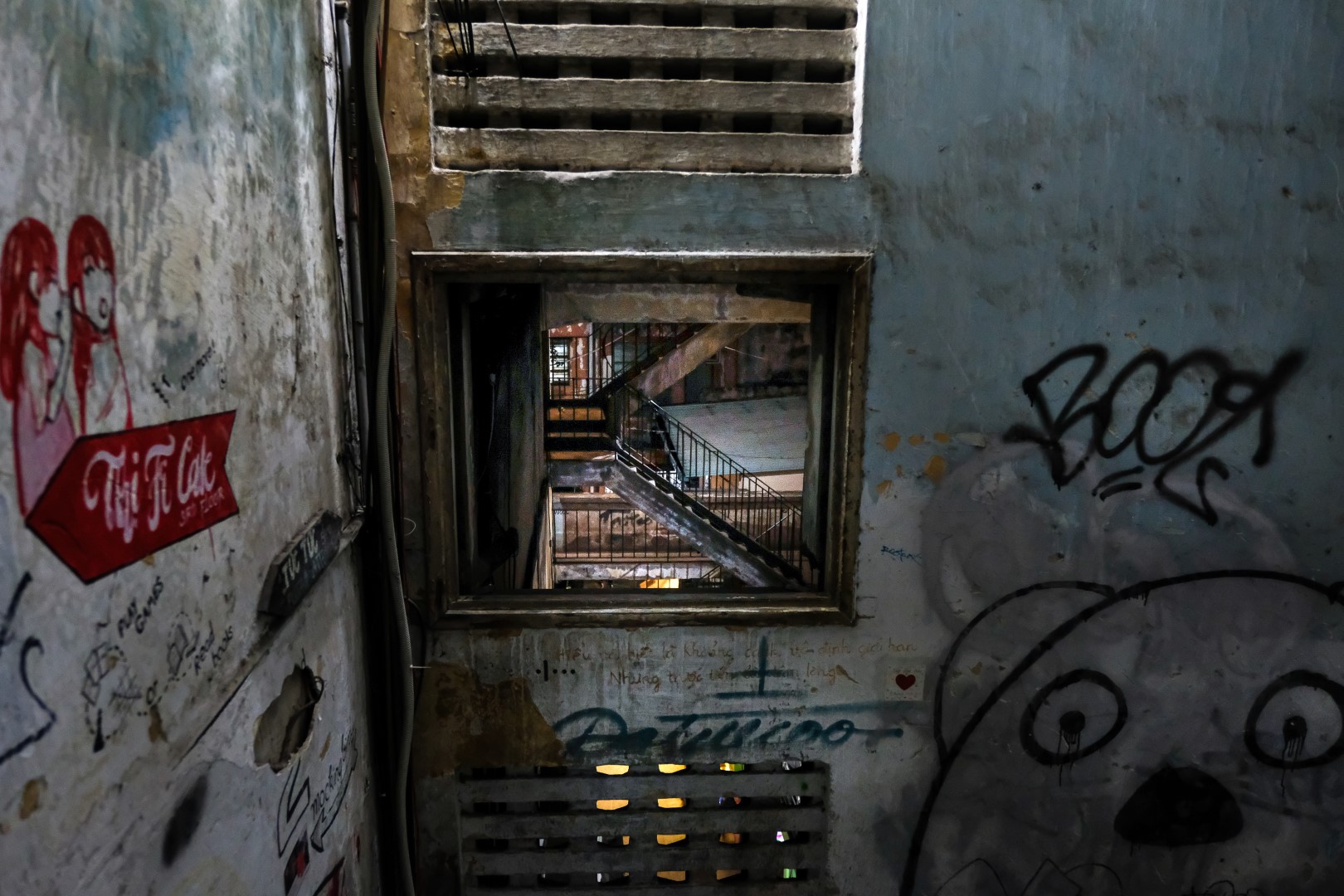

“I’m interested in cities where struggles for housing coincide with other problems,” says Michele Lancione: a woman dyes laundry in the polluted Makoko lagoon in Lagos, Nigeria.

Photo: Yasuyoshi Chiba, AFP

WOZ: Mr Lancione, where is the future of a city decided?

Michele Lancione: That’s not an easy question. And the first answer that comes to mind is: probably in a bank here in Switzerland.

Seriously?

No, of course that’s far too simplistic. I am not a Swiss expert at all. But the country is one of the most important locations worldwide in terms of financialisation, i.e. the transfer of capital into financial products, which in turn plays a central role in the development of cities and what we think of as urbanity.

How exactly?

Urban development and thus the further development of infrastructure just like housing do not only need capital. They are also designed for capital. They are designed to make even more money out of financial investments. The city is the place where this takes on a particularly concrete form, in infrastructure projects and a real estate economy that promises profits through mortgages and rents.

At the same time, the future of the city is also being decided from below, for example through processes of internal and transnational migration, which have brought about huge changes in the last forty years, especially for cities in the so-called Global South. Today, climate change also plays an important role, let’s think of the Indonesian capital Jakarta for example: parts of the city are subsiding by about 25 centimetres per year, flooding is increasing. This causes problems that are not decided in the context of financialisation – but in the experienced reality of the people who are forced to relocate. So the city is shaped as much by global economic interests as by the reality of the urban, the experienced struggle for housing. And there is a third level in between.

Politics?

Certainly, but I mean mainly a cultural understanding of a global political class that cities should look a certain way and function in a certain way. These three levels together result in the direction in which cities develop.

In your research, you have long been dealing with urban struggles over housing, with forced evictions and resistance to them. You describe this with the term “radical housing”. Where does it come from?

I don’t know exactly, to be honest. You can find it in pamphlets from housing movements in the UK in the seventies. As I understand it, and as my colleagues understand it, the radicalism that we use it to describe occurs particularly when movements are fighting the larger and broader issues that underlie housing in the first place. This can refer to economic mechanisms and profiteering, but also to completely different aspects.

Which ones, for example?

Sometimes it’s about climate justice, sometimes it’s about fighting racism or patriarchy. Most of my research so far has been done in Romania, especially in Bucharest. There I studied how people – especially Roma – fight for their right to housing. People, for example, who are evicted from their flats in the city centre. My focus was always on the struggle for the right to housing, but I found that it was about much more: it was a struggle of marginalised communities against racist dispossession. My new research project is now about examining in a number of cities around the world the social struggles with which the one over housing is interwoven.

The project started in September and is funded by the EU until 2025. What is the research goal?

We are trying to understand what people and communities are essentially trying to achieve when they struggle for a place to live in their city – sometimes without expressing it in language that is immediately accessible to us. We are investigating this in a number of cities in Africa, Asia, Central and South America. As a global research project, however, we try to avoid an overarching theory.

Why?

That would be problematic. We are dealing with geographically and also historically very specific contexts with different forms of political expression, which are not immediately understood in our very westernised academic world. It is therefore crucial that the researchers in this project are familiar with the relevant contexts and the forms of structural violence that operate there. The kind of knowledge that should come out of this project should not be: We have here overarching knowledge that can be derived from the housing struggles from Lagos to Mexico City. No, we want to provide a set of specifically locatable insights to enrich our collective knowledge of what the global struggle for housing actually is.

So you’re not creating a synthesised theory, but rather a kind of mosaic?

Yes, and I can explain why. Essentially, we want to create a decolonised scientific framework. Because the way the political in the struggle for housing has mostly been described so far stems from a Eurocentric tradition. It is perfectly fine to understand squatting in Italy as an essential practice of housing politics; but when people squat houses in Johannesburg, it probably takes a different form of expression than in Turin. One that has been hijacked in the past by certain narratives: humanitarian narratives, for example, that are about the resilience and adaptability of urban dwellers – and not about political practices. This is problematic because these narratives and this language come from the colonial centres. But sometimes the political is not just about organising or mobilising, but about multiple, nuanced forms of resistance that cannot be generalised – hence the mosaic approach.

Was it difficult to get public research funding with this approach?

I’ll be honest here: To a certain extent, you just have to play the game. The European Research Council (ERC), which is now funding my project, has a very neoliberal language. Then you have to say something like: this is a new paradigm of science, it’s groundbreaking. To get research funding, you also need a certain track record. It’s about how much and where you’ve already published – an exclusionary way of defining scientific excellence. But that’s how it works, and for better or worse, I fit into their scheme. At least the upside is that the ERC isn’t constantly breathing down your neck when funding is spoken for.

So as a professor you are a kind of door opener?

If you successfully apply for the research funds, you can hire the researchers yourself. When I got the grant, I was still at the University of Sheffield, but then had to return to Turin for family reasons. At the Polytechnic, I practically started the project all over again. And I found out: The research environment there is far less diverse than that in the UK. All around me were Italians, all white. One of the central prerequisites of the project is that people work in it who already know the respective contexts very well. So I hired people from Nigeria and Brazil. And it was a nightmare.

Why?

I spent a lot of time on bureaucracy. The system is simply not ready to hire international researchers. Mistakes were made with all the visas. It was a painful process to build this team of people with seven nationalities. Yet it was the only way to do this kind of work: I don’t want to send someone to Mumbai who was doing research on the real estate market in Rome yesterday. Because that would simply be reproducing what the vast majority of social sciences have always done.

How did you choose the cities?

I am interested in cities where struggles for housing obviously coincide with other problems. In Lagos, for example, there are two levels: First, financialisation is clearly a displacement driver; Lagos is the fastest growing city in Africa in terms of population and economy. Secondly, environmental and climatic factors play a role. Because most of the displacement is in the waterfront areas of the city.

You say that you are concerned with intersectionality, that is, with intersections of social struggles. Does housing have a prominent role in this?

I think so. After all, it is a place where we find our existential security as human beings. For me, whose interest is in cities and how people inhabit the world, housing is where an incredible number of things come together: Sexism, queerphobia, racism. Issues of how housing is granted or taken away from people. Economic issues. And it’s pretty obvious by now that the struggle for housing has become a global struggle.

Why now of all times?

Maybe it’s a bit oversimplified, but I think there are two reasons: first, the stark demographic reality. The world population has grown exponentially over the last fifty years. This inevitably brings with it questions about housing and infrastructure. Secondly, it is about the space in which capital has decided to multiply.

Where else? The lemon has been squeezed in many respects.

Exactly. And in actually every city – from Zurich to London and Belo Horizonte to Hong Kong – the primary need for housing has become the decisive growth factor. What this can mean was seen in Spain, for example, when the real estate bubble burst in 2008.

At the same time, it makes the functioning of capitalism very directly tangible for people from the most diverse backgrounds. It is all the more interesting that local and national authorities as well as international organisations and the UN are still dealing with this as if it were a simple local political issue. As if the problems could be solved with technical solutions. I have not investigated this further, but I suspect that this is being done deliberately. Because it is only by negotiating the right to decent housing in this way that capital can continue to do whatever – please excuse the language – shit it wants in urban centres.

Where does your passion for urbanity actually come from?

I grew up in the country, in a village eighty kilometres north of Turin. When I was eighteen, I moved to the city, a fairly small city, but a city nonetheless. In Turin, I started to get interested in questions around the urban. And of course I was also influenced by what I saw during my studies; there was an incredible amount written about urbanity back then.

Is it common to work with the concept of radicality in the academic world?

My colleagues and I use it to refer to militant communities that worked with the term “radical housing” because it was politically obvious. When it comes to housing, it quickly becomes existential and radical action becomes necessary. In science, my main concern is that knowledge must also be radical.

How is that to be understood?

It’s about the question of how you produce knowledge. About the decisions you make in the scientific context. It may sound silly that I have spent a year of my academic life hiring researchers who come from the context of their research. But it is a conceptual radicalism that is central in my eyes. It could make it possible to create a different kind of knowledge.

Or another example: six years ago we founded the “Radical Housing Journal”, in which we publish articles according to all scientific standards, but without letting ourselves be taken over by one of the big publishing houses. They take publicly funded academic work, privatise it and sell it back to the universities. Others even pay academics to publish with them.

They now call themselves “activist academics”. I guess that’s easier once you have a full professorship. Did you have to become more conformist on the way there?

If you publish well in the Anglo-Saxon system, you can have a fast career. I got my doctorate in 2012, and my first open ended contract as Associate Professor just four years later. And the reason was that I knew how to play the neoliberal game in the academic business. I am not ashamed to say that. Me and my partner, who is a filmmaker, were also very mobile; we lived in ten cities in three countries on two continents in less than eight years.

Where did you become an activist?

I was not yet a professor at the time, I was doing research in Bucharest as part of a post-doctoral position. I already knew the city very well and started to get involved with the Roma communities there – and that’s when the political caught up with me. I got to know feminist, anarchist, queer activist collectives – all personal matters close to my heart. And I had to learn to navigate the tensions between research and activism.

How does that work?

First, you have to be careful. It may be hip right now to call yourself an activist:n researcher: but there is a certain self-interest in the relationship. That’s why you should separate these two worlds quite strongly, because traditionally academics have always been very extractive towards activists, using them for their own purposes.

There is the same problem in journalism. What is your solution?

You must always be vigilant about your role – otherwise you risk exploiting activists for academic gain. Therefore, when I enter activist spaces, I either do it as an individual, as an activist; or I do it as an academic and in return I try to let resources flow from the academic enterprise into the activist struggles. When I call myself an activist researcher, it also refers, above all, to a critical attitude towards my own institutions. Today, as a professor, I have the opportunity to do this.

This was demonstrated last year when you publicly opposed the fact that the Polytechnic of the University of Turin, where you are employed, cooperates with the European border protection agency Frontex. What happened there?

The Polytechnic won a public tender from Frontex and now my department, where many cartographers and geographers work, is supposed to produce maps for the agency. I heard about it at a departmental meeting, and since then I have tried to fight it.

Did you succeed?

No, nothing could be done about the cooperation with Frontex. The department’s solution was to put a note in the contract stating that both parties are obliged to respect human rights. Which is of course complete rubbish, sorry. How can you ask Frontex to respect human rights? That’s madness. But at least there was some movement within the department, some colleagues took my side. And by writing an open letter to the public, it was at least noticed that not everyone in the scientific community agreed. It was encouraging for some activists, as well as for students who are grappling with the issue.

And how did the colleagues react?

The matter has caused quite a stir in the media, and for many people I am a stain on their reputations because of it. That also shows that the academic world today is largely depoliticised. A world in which young people study to pick up a degree and then have good job prospects – a functional thing for neoliberalism.

But many in the academic profession hardly have the privilege to expose themselves without consequences because many work under precarious employment conditions.

Yes, that is true. The professorship allows me to fight back. I feel it is a responsibility. But I am not the only professor at the Polytechnic. Just one of the few who speak out critically. And unfortunately that’s not only the case in Turin or Italy, many professors today are technocrats.

But there are always those who speak out clearly on political issues …

It is one thing to take a public stand, for example to co-sign an open letter, to get involved in debates. And that is also good! But it’s something else again to speak out against the academic establishment. Even if you have a full professorship, it’s not easy, because it can isolate you. I myself am on the safe side at the moment, I have my research project and my team. But what about 2025, when that ends? I wouldn’t suffer, but it would be difficult to work in an environment where I am spurned.

So should students in particular politicise the universities again?

That would probably be most effective. After all, we academics are mostly quite self-centred, we want to be liked. So if students build up pressure and start challenging their professors, they might hit a nerve. But I know from my own experience that you can’t expect that from students easily: I come from a working-class family, my father was a factory worker at Fiat, my mother a cleaner. When I arrived at the university, I first reverently accepted all hierarchies there. It is important for students to gain dominion over their own thinking and base the political on it.

—

Michele Lancione (38) is a professor at the Turin Polytechnic. He teaches at the Department of Economic and Political Geography of the Department of Territorial Studies and Planning. He is also Visiting Professor of Urban Studies at the University of Sheffield.

In his current EU-funded research project, Inhabiting Radical Housing, Lancione and a team of international scholars are investigating radical struggles over housing in a number of cities around the world. Lancione is co-founder and editor of the academic Radical Housing Journal and a member of the grassroots movement Common Front for Housing Rights in the Romanian capital Bucharest.