(The text below is a reasoning about the above video, which can be also watched here)

Today I woke up at 3am in order to get my flight back to Romania. I obviously was very tired tonight, having being around all day, but I decided to go to Vulturilor anyway. Good choice. Otherwise I would have missed the encounter with a very respectable Romanian politician: Mr Robert Sorin Negoiță.

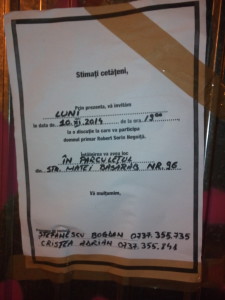

Negoiță is the Major of Bucharest’s Sector 3, where the Vulturilor st – and thus the Vulturilor case – belong to. Besides tired people, ruined tents, cold, and a provisional fire (things that belong to the realm of the usual in Vulturilor), one of the first thing that I noticed tonight was a flyer, posted on the iron fences separating people from their old houses. The flyer was calling people to take part to a public meeting, to be hosted in a public space (a park), attended by a public figure: our endearing Robert Sorin.

And so I went, together with one of Vulturilor’s family, which we will call ‘A’ family: mother, father and three beautifully noisy copii (kids). One thing should be said loudly and clear: Negoiță, as any respectable politician would do, was perfectly on time. Seven he stated on the flyer, and at seven he was smilingly taking off his SUV to be embraced by people. By his people. I mean, not the supporters: the bodyguards. A bunch of muscular bodies surrounding him from the very start, of which I will say in a minute.

And so I went, together with one of Vulturilor’s family, which we will call ‘A’ family: mother, father and three beautifully noisy copii (kids). One thing should be said loudly and clear: Negoiță, as any respectable politician would do, was perfectly on time. Seven he stated on the flyer, and at seven he was smilingly taking off his SUV to be embraced by people. By his people. I mean, not the supporters: the bodyguards. A bunch of muscular bodies surrounding him from the very start, of which I will say in a minute.

So Robert Sorin the Great takes off his SUV and is surrounded by people, and family ‘A’ is on the front line. They greet Mr Negoiță, they smile too, and here language is important: when they start talking to him they are very polite – so polite that for a moment I though ‘What the hell is wrong with them?’, ‘Why they do not jump on his head with more anger, having being in the street for almost 60 days?’. But no. Mother ‘A’ and father ‘A’ are just polite citizens inquiring their Major about their own situation: an eviction, which the Major and his predecessors have done nothing to avoid, which put them in the street beaten and dispossessed. So they ask. And it is their right to do so: it is a public meeting, public figure, etc. So mother ‘A’ says (more or less, but the meaning is there): ‘Mister Negoiță, find me a house, since I am on the street since two month, and I have four kids, please [the Romanian-polite version of ‘please’, ‘ve rog eu frumos’)

And Negoiță replies: ‘Are you from Vulturilor?’

Mother ‘A’: ‘Vulturilor 50’

Negoiță: ‘Why don’t you accept … [Pause]… What I have proposed you?’

Here we should recall what Negoiță has proposed to the Vulturilor people: a financial help to rent on the private market. Great, one could say. But one could say so only ignoring some simple facts: that the help is given only for 6 months; that it is not clear if the help is given per person or per family (a quite relevant detail, if you consider that many of these families are quite numerous); that for many of these people will be hard to find a place to rent, since they are Roma, full of kids, and with precarious working conditions; and that, in the end, to tackle a long-term structural problem (the lack of housing) with a short-term financial help is like curing cancer with paracetamol. In this sense, Negoiță’s offer is the classical political manoeuvre: it does not seek to solve the problem (a long-term solution for the evicted people) but only to claim that something has been done, or at least proposed. By refusing the offer, in the eyes of the public the evicted people end up refusing an act of benevolence, of help, and are immediately guilty of ingratitude. (Which is the most common plague for the ‘poor’: they are never satisfied, they are never happy, they want always more).

Here we should recall what Negoiță has proposed to the Vulturilor people: a financial help to rent on the private market. Great, one could say. But one could say so only ignoring some simple facts: that the help is given only for 6 months; that it is not clear if the help is given per person or per family (a quite relevant detail, if you consider that many of these families are quite numerous); that for many of these people will be hard to find a place to rent, since they are Roma, full of kids, and with precarious working conditions; and that, in the end, to tackle a long-term structural problem (the lack of housing) with a short-term financial help is like curing cancer with paracetamol. In this sense, Negoiță’s offer is the classical political manoeuvre: it does not seek to solve the problem (a long-term solution for the evicted people) but only to claim that something has been done, or at least proposed. By refusing the offer, in the eyes of the public the evicted people end up refusing an act of benevolence, of help, and are immediately guilty of ingratitude. (Which is the most common plague for the ‘poor’: they are never satisfied, they are never happy, they want always more).

Father ‘A’ wants something more – more than being an evicted homeless guy. There is a passage in which he clearly states who he is and who he wants to be. He simply states: ‘We work. We pay’.

And here Negoiță replies, brilliantly: ‘Since you work and pay you should rent a flat!’

Father ‘A’: ‘But where?’

Negoiță: ‘The city is full of those!’

Father ‘A’: ‘The city is full… Where?’

The city is full of flat to be rented: Negoiță is right. But he is not portraying the full picture here. Let’s take the following, hypothetical case, as example. You are a researcher coming from the UK and you want to rent a flat in Bucharest. Easily 50% of the housing market is too expensive for you – you with an average income that is at least 5 times that of a Romanian researcher. So you turn your attention to the other 50%. Within this 50%, after many days spent looking around, making phone calls, and many useless appointment, you find a place that could work. In order to rent it, you have however to pay for the first month in advance, to give a deposit equivalent to one month, and to pay a lump-sump to the agent that has brought you to the place. This is a lot of money, even if you are a researcher coming from the UK. Now let’s take the same situation changing characters. Instead of the researcher you have ‘A’ family, composed by two adults having a provisional informal job, and three kids that make noise like a bunch of drunker in an open-air discotheque. Moreover, ‘A’ family does not come from the UK, but belong to the most neglected ethnic minority of the country (and possibly of Europe). Finally, they do not have the luxury of looking for an house while living in a hotel, surfing the web sipping a cold beer – but they have to do so while living in a tent, pissing in an empty parking lot, wearing the same clothes for days, etc. Indeed, Negoiță is right. The city is full of flats to be rent. But there are not enough ‘right’ people that could eventually rent them.

The city is full of flat to be rented: Negoiță is right. But he is not portraying the full picture here. Let’s take the following, hypothetical case, as example. You are a researcher coming from the UK and you want to rent a flat in Bucharest. Easily 50% of the housing market is too expensive for you – you with an average income that is at least 5 times that of a Romanian researcher. So you turn your attention to the other 50%. Within this 50%, after many days spent looking around, making phone calls, and many useless appointment, you find a place that could work. In order to rent it, you have however to pay for the first month in advance, to give a deposit equivalent to one month, and to pay a lump-sump to the agent that has brought you to the place. This is a lot of money, even if you are a researcher coming from the UK. Now let’s take the same situation changing characters. Instead of the researcher you have ‘A’ family, composed by two adults having a provisional informal job, and three kids that make noise like a bunch of drunker in an open-air discotheque. Moreover, ‘A’ family does not come from the UK, but belong to the most neglected ethnic minority of the country (and possibly of Europe). Finally, they do not have the luxury of looking for an house while living in a hotel, surfing the web sipping a cold beer – but they have to do so while living in a tent, pissing in an empty parking lot, wearing the same clothes for days, etc. Indeed, Negoiță is right. The city is full of flats to be rent. But there are not enough ‘right’ people that could eventually rent them.

However, this is just part of the story. The reason why I am so glad that I went to this public meeting is not because I finally saw Negoiță’s smile (all my pleasure, really), but because I felt, bodily felt, the violence of a State, of a City and of a Town Hall that do not care about their people, do not care about dialogue, but simply try to harass and control; to appear and to hide; to go straight without ever turning back. I invite you to look closely at the short video posted above. Beside the bare fact that Negoiță run away as soon as ‘A’ family started questioning him – therefore reducing his public meeting to a matter of minutes – there are other interesting details to highlight. Have you noticed the numerous shoulders and harms that appeared in front of my camera as soon as I started filming the exchange? Did you pay attention to the flashes fired directly into my camera’s objective, in order to disrupt the filming? Did you see the guy stretching his harm in front of me, tactically impeding me to film? Or have you paid attention to the cohort of three-four guys whom, like a human wall, impede me to follow Negoiță’s escape? What surely you could not notice from the video are the numerous kicks, the bumps on my backpack, the two tackles I received from the back, the people suddenly crossing my path thus impeding me to move, and the overall bodily pressure ‘to stay back’, to do not advance, to be in place. A place, that of ‘A’ family and I, which obviously should not be the same as Negoiță’s.

However, this is just part of the story. The reason why I am so glad that I went to this public meeting is not because I finally saw Negoiță’s smile (all my pleasure, really), but because I felt, bodily felt, the violence of a State, of a City and of a Town Hall that do not care about their people, do not care about dialogue, but simply try to harass and control; to appear and to hide; to go straight without ever turning back. I invite you to look closely at the short video posted above. Beside the bare fact that Negoiță run away as soon as ‘A’ family started questioning him – therefore reducing his public meeting to a matter of minutes – there are other interesting details to highlight. Have you noticed the numerous shoulders and harms that appeared in front of my camera as soon as I started filming the exchange? Did you pay attention to the flashes fired directly into my camera’s objective, in order to disrupt the filming? Did you see the guy stretching his harm in front of me, tactically impeding me to film? Or have you paid attention to the cohort of three-four guys whom, like a human wall, impede me to follow Negoiță’s escape? What surely you could not notice from the video are the numerous kicks, the bumps on my backpack, the two tackles I received from the back, the people suddenly crossing my path thus impeding me to move, and the overall bodily pressure ‘to stay back’, to do not advance, to be in place. A place, that of ‘A’ family and I, which obviously should not be the same as Negoiță’s.

But there is one more thing that is impossible to get from the video: this is the overall affective atmosphere of the place. For a moment I felt in danger – the eyes, the hands, the kicks, the muffled words. I felt in danger for ‘A’ family, which courageous exposed themselves in that meeting, and for the kid I was carrying by hand during the all duration of the video. What could have happened if I would have run toward Mr Robert Sorin Negoiță? Would have his bodyguards – who were dressed in civil clothes, such that one could not distinguish them from the crowd – allowed me and the kid to safely arrive at destination? Would have this man, this Major, this public figure, accepted a civil questioning? I did not had the chance to prove him, since he surrounded himself with men purposely trained to safeguard him from such endeavour.

But there is one more thing that is impossible to get from the video: this is the overall affective atmosphere of the place. For a moment I felt in danger – the eyes, the hands, the kicks, the muffled words. I felt in danger for ‘A’ family, which courageous exposed themselves in that meeting, and for the kid I was carrying by hand during the all duration of the video. What could have happened if I would have run toward Mr Robert Sorin Negoiță? Would have his bodyguards – who were dressed in civil clothes, such that one could not distinguish them from the crowd – allowed me and the kid to safely arrive at destination? Would have this man, this Major, this public figure, accepted a civil questioning? I did not had the chance to prove him, since he surrounded himself with men purposely trained to safeguard him from such endeavour.

What happened tonight is sad. I wish more cameras and more people were there, to catch the details of an only namely ‘public’ machine that does not allow its own citizens to peacefully question their Major. What happened tonight is sad because one should not fear such public events.

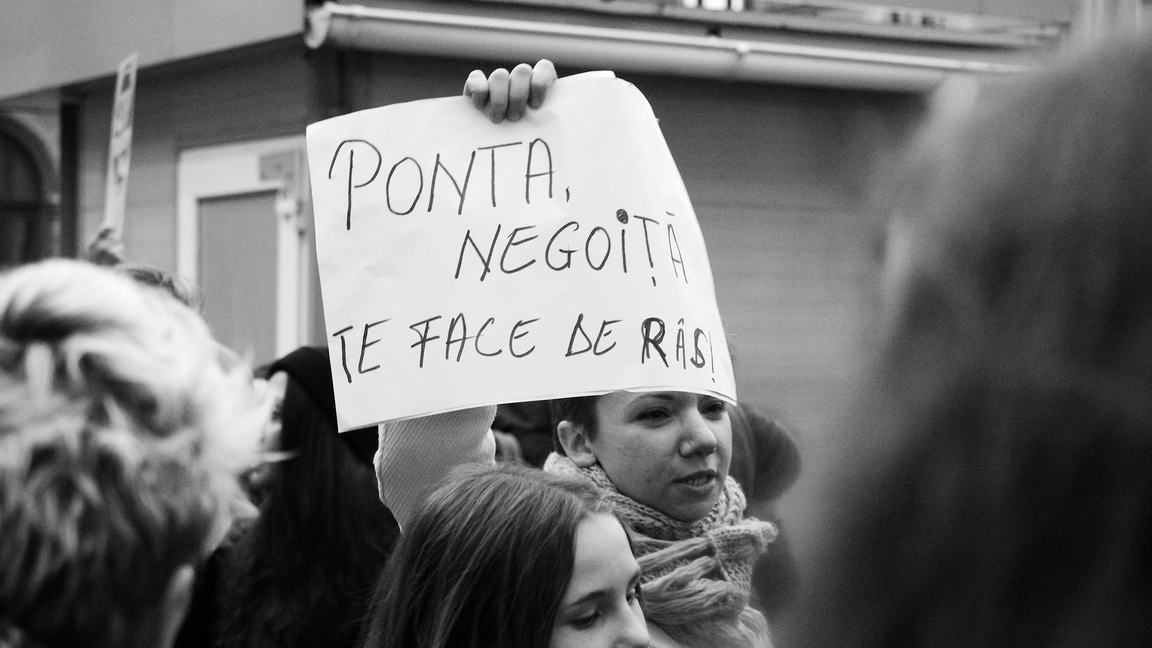

In Italy, when I was younger, I attended many public protest against the extreme rights and other fascist movements. At the time it was easier to see the enemy, to tackle it, and to defend oneself. Tonight I felt that the enemy here – in the Vulturilor case and possibly not only – is subtler, less evident, but still ready to let its violence (being that verbal or physical) to be discharged. I invite Mr Negoiță to prove me wrong: let’s have a true public meeting, one in which we can discuss the point listed above, without the need for someone’s body to intrude, to stop, to control. I do not know if this is going to happen. What I know is that tonight was a short, sad, night but also one that charged me with hope. Look at what ‘A’ family can do. I felt in danger, but is Negoiță the one who run away. And this is only thanks to ‘A’ family. One of the many families struggling against the madness of eviction and the nonsense of a privatize public realm.

I wil tell you the story of that place.i lived there untill 1972.it was a jewish neighbourhood ,an elite one i would say.We had a lot of neighbours who had graduated univeristies not in Romania but in Germany or other places.Kids were mostly studying a musical instrument in the spare time and life had a certain flow that has nothing in common with what is now .ok.Autumn oF 72 i moved and by now a lot of the jews were let to leave for Israel because the state (socialist) took some money for this from Israel.in many of the remaining houses in the neighbourhood were put not teachers or doctors or even workers but gypsyes.why?probably the socialist leadership knew that they would ruin the houses so demolition would follow.Anyway…as i was taking a walk from time to time i saw the total damageof the housese that was increasing from year to year(broken windows ,etc) and felt really sorry,as i knew exactly what kind of people lived there before.Now they are evicted.I know that psecific place from forever and it is unapropiate to be lived anymore now,as it was allways the wors place there.who brought the things to this level?The inhabitants aka the evicted families.So problem is a bit much more complex than it seems.P.S.those houses had original owners beeing really old houses.

Thank you so much for sharing your story – it is indeed very interesting and relevant. We should not forget, however, that the problem here is that these people have been evicted and that the Primarie has done nothing for them. We may discuss about the right or not for them to live there, but the Primarie knew of the eviction from 2008 – and nothing has been done since then. Anyway – thanks: and if you want to share more detail about your story please write to me – ml710@cam.ac.uk